- Podcast Features

-

Monetization

-

Ads Marketplace

Join Ads Marketplace to earn through podcast sponsorships.

-

PodAds

Manage your ads with dynamic ad insertion capability.

-

Apple Podcasts Subscriptions Integration

Monetize with Apple Podcasts Subscriptions via Podbean.

-

Live Streaming

Earn rewards and recurring income from Fan Club membership.

-

Ads Marketplace

- Podbean App

-

Help and Support

-

Help Center

Get the answers and support you need.

-

Podbean Academy

Resources and guides to launch, grow, and monetize podcast.

-

Podbean Blog

Stay updated with the latest podcasting tips and trends.

-

What’s New

Check out our newest and recently released features!

-

Podcasting Smarter

Podcast interviews, best practices, and helpful tips.

-

Help Center

-

Popular Topics

-

How to Start a Podcast

The step-by-step guide to start your own podcast.

-

How to Start a Live Podcast

Create the best live podcast and engage your audience.

-

How to Monetize a Podcast

Tips on making the decision to monetize your podcast.

-

How to Promote Your Podcast

The best ways to get more eyes and ears on your podcast.

-

Podcast Advertising 101

Everything you need to know about podcast advertising.

-

Mobile Podcast Recording Guide

The ultimate guide to recording a podcast on your phone.

-

How to Use Group Recording

Steps to set up and use group recording in the Podbean app.

-

How to Start a Podcast

-

Podcasting

- Podcast Features

-

Monetization

-

Ads Marketplace

Join Ads Marketplace to earn through podcast sponsorships.

-

PodAds

Manage your ads with dynamic ad insertion capability.

-

Apple Podcasts Subscriptions Integration

Monetize with Apple Podcasts Subscriptions via Podbean.

-

Live Streaming

Earn rewards and recurring income from Fan Club membership.

-

Ads Marketplace

- Podbean App

- Advertisers

- Enterprise

- Pricing

-

Resources

-

Help and Support

-

Help Center

Get the answers and support you need.

-

Podbean Academy

Resources and guides to launch, grow, and monetize podcast.

-

Podbean Blog

Stay updated with the latest podcasting tips and trends.

-

What’s New

Check out our newest and recently released features!

-

Podcasting Smarter

Podcast interviews, best practices, and helpful tips.

-

Help Center

-

Popular Topics

-

How to Start a Podcast

The step-by-step guide to start your own podcast.

-

How to Start a Live Podcast

Create the best live podcast and engage your audience.

-

How to Monetize a Podcast

Tips on making the decision to monetize your podcast.

-

How to Promote Your Podcast

The best ways to get more eyes and ears on your podcast.

-

Podcast Advertising 101

Everything you need to know about podcast advertising.

-

Mobile Podcast Recording Guide

The ultimate guide to recording a podcast on your phone.

-

How to Use Group Recording

Steps to set up and use group recording in the Podbean app.

-

How to Start a Podcast

-

Help and Support

- Discover

Building a movement that can take full advantage of the IRA

The Inflation Reduction Act is ambitious climate policy, but history shows that ambitious policy is not always followed by ambitious implementation. In this episode, Hahrie Han of Johns Hopkins University and David Beckman of the Pisces Foundation talk about Mosaic, a grant-making coalition that aims to help build a robust movement infrastructure to ensure that vulnerable and underserved groups can take full advantage of the significant funding offered by the IRA.

(PDF transcript)

(Active transcript)

Text transcript:

David Roberts

For all that has been written about the Inflation Reduction Act, the most salient fact about it remains widely underappreciated. What is significant about the bill is not just that it sends an enormous amount of money toward climate solutions, but that the money is almost entirely uncapped.

The total amount of federal money that will be spent on climate solutions via the IRA will be determined not by any preset limit, but by demand for the tax credits. The more qualified applicants that seek them, the more will be spent. The Congressional Budget Office estimated the bill’s spending at $391 billion, but a report last year from Credit Suisse put the number at $800 billion and a more recent Goldman Sachs report put it closer to $1.2 trillion.

Big companies will have teams of lawyers to tell them when they qualify for the tax credits, but there are also billions of dollars in the IRA that are meant to be spent on vulnerable and underserved communities. Those communities do not typically have teams of lawyers.

Who will work to enable them to take full advantage available of the money? Getting that done will require campaigns, relationships, and grassroots mobilization. It will require movement infrastructure.

A relatively new grant-making coalition called Mosaic is attempting to help build that infrastructure by dispersing money to the frontline organizations that comprise it. Mosaic is a cooperative effort among large national environmental groups like NRDC, big foundations, and various smaller regional, often BIPOC-led groups.

It has pooled philanthropic money and thus far given almost $11 million of it to dozens of relatively small groups and campaigns — 85 percent of them BIPOC-led, 87 percent of them female-led — selected by a governing committee from well over a thousand applicants. The governing committee contains a super-majority of representatives from frontline communities; the foundations have a super-minority.

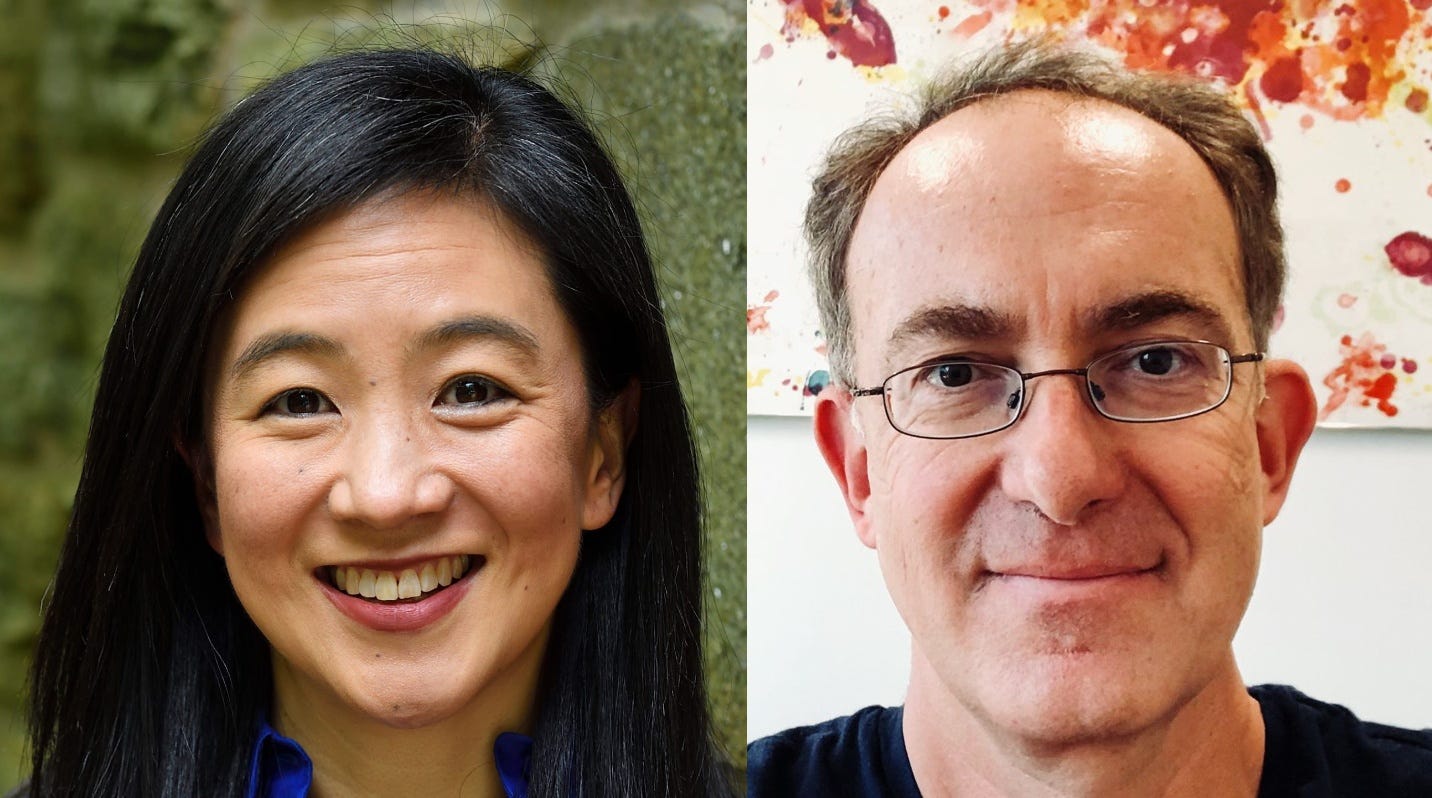

To discuss the need for movement infrastructure, the Mosaic effort, and the possibilities IRA offers for frontline communities, I contacted Dr. Hahrie Han, a professor of political science at Johns Hopkins University, and David Beckman, one of the founders of Mosaic and the current president of the Pisces Foundation. We talked about what movement infrastructure is, the failure of the climate movement to build enough of it, and Mosaic’s theory of change.

So, without any further ado, Hahrie Han and David Beckman. Welcome to Volts. Thank you so much for coming.

Hahrie Han

Thanks so much for having us.

David Beckman

Yes, thanks David.

David Roberts

I want to start with you, Hahrie. You have written in the past, and one of the themes of your work is that social welfare legislation or policy can often fail to reach, let's say, its full potential if there isn't the sort of civic and movement infrastructure around it to help it succeed. So maybe you can just talk for a little bit about what do we mean by infrastructure here? What does infrastructure mean? And maybe also what I think would be helpful is maybe you could cite some examples of times you think legislation or reforms fell short of what they could have done because of a lack of infrastructure.

And then maybe some examples of when there was infrastructure and that was helpful.

Hahrie Han

Yeah, I think that's a great question. There are so many instances when in trying to tackle some of our stickiest social problems, we put an enormous amount of attention and effort into trying to build the coalitions that we need to pass the policies that we want. If we think about any of the landmark legislation that we've had in recent decades, from the Affordable Care Act to the IRA to any other of these big kind of efforts, they've taken years or decades even to pass because of all the work that it takes to get them through. But then what so much research and so much history has taught us is that if there isn't the same kind of effort that goes into the implementation, that the gains that we made with policy alone are really fragile.

There's one famous book that looks at some of these gains, these policy wins, and calls them a "hollow hope" if they're not accompanied by the kind of infrastructure that you're talking about. And we just have a lot of those kind of examples throughout history. So to give a couple of them. For example, this book, "The Hollow Hope," starts with landmarks court legislation like Brown v. Board of Education, where, if you actually look at the ability of that one decision by the Supreme Court to actually translate into integration on the ground. It didn't actually achieve its goals, and its actual outcomes felt really hollow until you saw this mobilization of a lot of the school districts and parents and communities on the ground to make real the promises that were in that Supreme Court hearing.

David Roberts

That particular example is kind of telling since that infrastructure withered a little bit and now those gains are being reversed. So it's not just a one time thing like sort of implementing it and making it real is perpetual effort.

Hahrie Han

Yeah, I think that's a great point, right, because the thing that I always like to remind people is that any policy gains that we have are really fragile because they can always be reversed on the one hand, as you point out. But then also because oftentimes when policy gets implemented, it drifts away from what the original goals are. There's a famous political scientist, Jacob Hacker at Yale who looked a lot at basically welfare policy and a lot of social policies. And what he finds is that if you look at the impact of those policies on people's lives, that often there's a big gap between what legislators intended and what actually happened because of that process of drift.

And that I think is also a really important point because what it tells us is that you don't need Congress to take another action to reverse policy gains, but in fact, it can just be ignoring a process that can lea to that kind of drift.

David Roberts

Entropy, basically. Like if you're not continually reinforcing it, it naturally will start to erode.

Hahrie Han

Yeah, exactly. That there's just kind of natural chaos in the system. Or sometimes there are people that are actively working to undermine the ability to achieve those goals.

David Roberts

Yes.

Hahrie Han

Totally.

David Roberts

And they never quit. And they seem to have great infrastructure. If I could just insert one of my perpetual gripes in there. Like infrastructure working against social welfare legislation is just robust and seemingly permanent.

Hahrie Han

Yeah, it's easier to stop something than to create something new. And it's also easier to organize people around their prejudices and to organize people around hope.

David Roberts

Yes, indeed. So what are some examples then of the other side where sort of the infrastructure has come together around a law and made it?

Hahrie Han

So one example that I like actually is the Community Reinvestment Act, which is not a perfect act by any stretch of the imagination. So I know that there are lots of ways in which we wouldn't necessarily hold it up as a paragon of legislation.

David Roberts

Can you tell us what that is?

Hahrie Han

Basically, the Community Reinvestment Act was passed essentially to try to stop redlining in poor and Black communities. And so when it first began to come out in 1970s, 1980s, a lot of banks weren't lending to certain communities because they would literally draw red lines around neighborhoods where they wouldn't make investments. The Community Reinvestment Act was passed as a way to try to stop that redlining. One of the things that was really important that they did in passing the Community Reinvestment Act is that they essentially created these mechanisms through which communities could have continual oversight over the way that banks were acting.

And so the Community Reinvestment Act essentially created these boards that were an accountability mechanism for banks. And alongside the Community Reinvestment Act, there was a bill called the Home Mortgage Data Act. HMDA, it's what it's called for short. And what HMDA did was it made available the data that these local communities would need to be able to look in and see whether or not the banks were making investments in the ways that they should. So that alone doesn't actually cost government a ton of money. But by creating that accountability mechanism, what it did was create this ongoing hook, essentially around which communities could organize and essentially hold banks accountable.

And so over time, we've seen trillions of dollars of investments being driven into lower income communities because of the Community Reinvestment Act.

David Roberts

And so what do we mean then? I mean, we're talking about infrastructure here, sort of vaguely. What do we mean concretely by having the infrastructure in place to make these laws perform the way we want? What is it comprised of?

Hahrie Han

So, that's that's a complicated question. In my mind, movement infrastructure has a lot to do with the relationships, with the structures and the vehicles and the resources that a movement needs to be able to respond to the kind of strategic challenges that are going to come its way. And so I think one mistake that people make a lot in thinking about movements is to think about the most effective movement as being the one that has the best plan at the beginning. But actually, what we find is that the most effective movement is the one that can best respond to the contingency that comes up that it didn't expect.

And what do you need to respond to contingency? Well, you need to have strong leaders, good people who are interconnected with each other. You need to have resources that you can deploy. You need to have vehicles that can move nimbly and agilely in response to things that might come up that you don't expect. There are a range of those kinds of things that I think comprise the movement infrastructure that enable that response.

David Roberts

David, let's go to you for a second. The Mosaic effort is an effort to build this kind of infrastructure. So I want to talk about what that infrastructure is, but let's back up a little bit. Mosaic is a coalition of all these big, long-time foundations and big green groups that have come together with the sort of explicit goal of changing the way environmental philanthropy is done. So let's start then, with that. What is wrong with environmental philanthropy? Why does it need to change? What are its sort of flaws and shortcomings today?

David Beckman

Well, that's a big question, too. Let me just say about Mosaic. It is really the name hopefully paints a picture of the idea and the theory, which is that it's not just the big organizations, but it's all of the organizations and the people, the activists and the advocates that are individually doing important work but are not collectively able to keep pace with the extraordinary challenges and the opponents that you referred to. They can do better in a more connected fashion. And what's been missing is the investments in that connectivity and the tools that Hahrie discussed. And we can talk about what they mean in the context of the IRA.

But part of the reason that those tools that are so essential to movement success are missing is because, in the main, big philanthropy hasn't invested in them. Bridgespan, one of the leading social sector consultancies, has published a whole report about how field building, which is another way of looking at this, is one of the most effective, yet underinvested strategies in philanthropy. So this is an endemic problem, I think, that has a lot to do with the fact that infrastructure is so important, but it's invisible in some sense. It's not vivid. It isn't like you can't take a picture of the forest that you've saved.

It's the conditions, the how that you get to that result.

David Roberts

Right, it's not obvious also what the metrics are, right? Like, if you're doing it right or not, it's not clear what you're it's difficult to measure.

David Beckman

That's right. It's difficult to measure. So your question about philanthropy, of course there's lots of different philanthropies and there's more coming on the scene happily every day. But in the main, big environmental philanthropy funds in an atomistic way. It funds narrowly. It funds in a way that is exclusive instead of inclusive, and it tends to concentrate power. So four aspects that are not well suited to big scale social change and not well suited to implementing something of the scale of the IRA. And let me just give you a couple of facts about this. The atomistic part is really concentrating resources in single organizations and not building the fields that make them stronger.

The connections that Hahrie is talking about narrow. In 2018, the Environmental Grant Makers Association, which is not an association of every environmental funder, but many of the really large ones, surveyed its members and found that just 200 nonprofits of the perhaps 15,000 that focused on the environment got over 50% of the $1.7 billion that its members donated in 2018. And that is astounding, if you think about it, 15,000 or so registered 501(c)(3)s and 200 are getting half the money. And that year, five nonprofits got 13% of that $1.7 billion funding pie. The Nature Conservancy, World Wildlife, EDF, and the place I used to work, NRDC, four of those got $100 million dollar grants from the Bezos Earth Fund a couple of years later.

So you've got deep concentration. And then BIPOC organizations are funded at just a fraction between, say, 1% and 10%, depending on the study you look at. So there's not an inclusive focus. And last, something we're trying to address with Mosaic, most of the decisions are made by program officers and boards. Relatively few people with a certain type of demographic background, usually not always. And so there isn't much investment in participatory grant making, which is what we're modeling with Mosaic, where leaders actually get to compare and to cogenerate strategy and then to deploy money themselves as opposed to having to ask for it from a philanthropy.

So atomistic narrow, exclusive and concentrating isn't a recipe for success in general, and certainly not with respect to the IRA.

David Roberts

This is so reminiscent like this is a critique of left versus right philanthropic funding that goes back decades, since I remember paying attention. It's always the right is investing in infrastructure, right in the organizations, in the relationships. Like, you look at the Federalist Society that is basically all about relationships and look at the tentacles it has sent out into US society, just remarkably successful. And then you hear people on the left saying, "I can get a grant for a particular campaign or a particular accomplishment or a particular policy, but it's impossible to get just operational funding, just basic funding for my organization to survive."

And those who do get it, as you say, are so concentrated, and when a single group gets so much money, it creates this perverse incentive for the group to sort of put its own interests first, right, to keep getting the money. So you get almost a resistance to cooperation and a resistance to working with others.

David Beckman

Yeah. Well, the competition for money I have experienced myself when I was an advocate and lawyer doing environmental justice work and water advocacy and the things I did at NRDC, there's no question that it gets in the way. And part of the problem is there's not enough money because the organizations I mentioned, I think, are good organizations. So the issue isn't that they shouldn't be funded. It's that everyone else needs to be funded, too. And money needs to flow in ways which are both equitable and fundamentally effective for large scale social change and philanthropy in the main.

Not always, but in the main has missed that. And that's a big problem.

David Roberts

I wanted to ask kind of a practical question about Mosaic. So you have this grant making board, this representative board that has a lot of diverse people on it, and you have over 1000 relatively small scale applicants and what sounds like a really labor intensive process by which all these applicants are vetted. And the board discusses them with one another and they're winnowed down and et cetera, et cetera. I mean, I was reading about this in The Chronicle of Philanthropy or whatever the heck it's called, and it just sounds exhausting. People involved were saying it's exhausting.

It's like finals week all year. And yet the result of that is $11 million, which is, in the context of these small groups, obviously nothing to shake a stick at. But like Bill Gates, it's just dropping $100 million here and there on this and that company. So I'm just asking about, I guess, the ratio of soft costs of work, of time intensiveness versus the amount of money that's being deployed. Do you think that's sustainable in the long run?

David Beckman

Yeah, it's a good question. Well, the good news is that Mosaic is about to announce $10 million in additional funding. So it's a new effort that is beta testing a lot of the concepts that we're talking about and learning along the way. So I've been able to participate, which is a really interesting experience as somebody who also spent a decade and a half as an advocate and then runs a foundation, a private foundation that's in a more traditional mode. And it's true it takes a lot of time, but I'll tell you, it takes a lot of time the other way, too.

So it's not really a question so much of how much time, but what is the quality of the time that's invested. And I think the benefit of participatory grant making that I see, particularly when it's done well and leaders are involved, is that it itself is infrastructure. There are relationships that are formed, ideas that are exchanged, trust that is built, theories of change that are debated. And the environmental movement, as you know, both of you know, is fractious and doesn't always agree with each other. And so there's a value there that I think is differentially impactful compared to several program officers or one making decisions.

Should there be more money in participatory grant making? Absolutely, and in fact, there's a study that says that just a fraction of foundations participate in any way with grant making approaches that devolve power to other people. And I think that's partly because there's not a lot of good examples of where it's worked. So hopefully, one of the things that Mosaic and other efforts can do is to demonstrate the benefit of this approach for others.

David Roberts

Can you just very briefly describe the approach? It's a committee and there are meetings. Is there more to it than that?

David Beckman

Yeah, it's just like a meeting, David. There are a couple of things. First of all, the application process seeks collaborative proposals. So that in itself is different. Usually, in my experience, it's like a single NGO approaching a single foundation. So already, from the beginning, the proposals are done in a different way. They're done online, they can be done verbally, which I think is a really good progressive approach. There's no long 15-page proposal that is required. So that's an attempt to lower the barriers of entry. And then there's this fabulous staff that has incredible data crunching capacity, that looks for heat maps and does some initial vetting.

And then the leadership that makes the decisions is not involved in all of that. So it's not that everybody's engaged at that stage. But then we met in for three days and went over, did a whole kind of retreat, and reviewed the top section of proposals that the staff had prepared. And that was a debate like some of the best debates I've been involved as an environmental advocate, where people are talking about what is needed, where how do you compose a grant slate that's equitable and effective? How do you fund the grassroots? How do you fund relationships between the Big Greens and others, networks and communications and the rest?

So what comes out of it? I think and I can compare because I run a foundation, I think is a really good way to approach things that really deserves a place much more solidly in the mainstream of environmental grant making.

David Roberts

Hahrie from your perch as Mosaic is sifting through all these applicants, what kinds of things should it be looking for? What are the ingredients of this sort of movement infrastructure that you're talking about that you can identify in groups? Are you looking for certain kind of people, certain kind of strategies, certain kind of goals or financial structures. How would you go about building movement infrastructure? What are the sort of indicators that you're looking for among grantees?

Hahrie Han

It's a great question. So I think that in thinking about movement infrastructure, in the end what we're trying to do is identify individuals and organizations that aren't just the kind of individuals and organizations that can do a thing, but that can become the kind of people that do what needs to be done, right? And so this kind of gets back to the idea that when you're thinking about implementing a bill as large as the IRA or building a movement as broad as what we need in the environmental movement, you have to anticipate the fact that there are going to be challenges coming your way. You can't anticipate.

And so I have to think about who are the kind of people that are going to be able to respond to that? What are the kind of organizations that can respond to that? And so then how do I actually think about and identify that at time one without knowing what the challenges are that they're going to be investing in time two?

David Roberts

Yeah, exactly.

Hahrie Han

The things that would look for would be things like what is the extent to which they're building networks among their people that are bridging versus just bonding. And so the idea of a bonding network is one in which people are connected to other people who are a lot like them. Bridging networks are ones that not only create those bonds, but also enable people to bridge across to different kinds of people who aren't necessarily like them. And so what that means is that you have an organization that's constantly growing and renewing itself. I would look for organizations that are investing in building a kind of inclusive leadership in the way that David was describing, partly because I think obviously there are moral reasons why we would want to make sure that we have an inclusive leadership, but partly also for strategic reasons.

There's a lot of research that shows that the movements that can best anticipate and respond to contingency this is true not only for movements, but actually for corporations as well are ones that have lots of different kind of for lack of a better word, kind of sensors out in the community to sort of understand what are the changes that are coming our way and how do we figure out how we can anticipate, how we need to remake ourselves for the future. And so if you don't have that kind of diversity of people giving you input, then you're not able to respond nimbly to the constantly changing world around you. So there are a lot of things like that that I think begin to give us a sense.

David Roberts

Yeah, I think this is such an important point and maybe I'll touch that back to you also, David, because I feel like and I've done a couple of pods on this recently, been thinking about it recently and this idea of trying to fund a more diverse give money to more diverse groups and et cetera. It's so often framed in terms of sort of representation as kind of an end in itself, like a moral good in itself. It's just good to have other people there because you want to check the box. But the point of all this and this is the point that comes across in management literature and all this is not just that it's good, but that diverse groups make better decisions.

It's an improvement in your ability to do good things. It's not just for looks or not just for box checking. It makes you perform better. And I wonder David, if you've you know now that you've really gotten your hands dirty trying to assemble a group like this, I wonder your thoughts on that, if you found that to be the case.

David Beckman

Absolutely. And I would just to add to what you said a second ago for many grant makers, again, not all, but I see and hear a lot that makes me think that equitable grant making for some is their charity, not their strategy.

David Roberts

Right. Yes.

David Beckman

And there's a big difference. There's a big difference. There's certainly a moral imperative to fund communities and people who have more than their fair share of problems and who have been deprived of money from big institutional funders historically. So that stands on its own. But the point you're making is not only I think about the fact that better, more creative and interesting solutions come up which do, but that you can build power that way. As Hahrie's pointing out by bridging between what could be sort of atomistic, semi-competitive or worse, communities within a movement and to find some sort of working relationships, if not stronger relationships, productive relationships that allow big, important social change to happen.

And that I think is one of the most important things that's missed when we pick fractions within a movement, either the Big Greens if you're talking about the environmental movement or frontline organizations, I think both can play a role and they can play a synergistic role when their collective impact is built on some relationship. And sometimes that isn't that we're going to totally agree, it's not kumbaya, let's all get along. It's that often when you're in relationship and you're in those rooms you can find that you might disagree about two or three things and maybe those are not going to get resolved but there's three or four things that you can agree on and through that kind of doorway you can make progress that you couldn't make otherwise. And that's why some of the effort in answering the question you asked earlier I think is worth it because it's not just process or overhead, it is actually the work, it is actually the infrastructure.

David Roberts

Another question for you Hahrie is about backing up from the implementation, just the legislation itself. It seems to me like not only should environmental philanthropists be thinking in terms of infrastructure and implementation, but obviously legislators should too. Like, you can do better or worse in the text of a law on those terms. And this is something I feel like this is another critique of Democrats that goes way back, which is that they don't lose well, right? Like they don't lose in a way that improves their chances the next time. And even when they do pass legislation, it's not like always part of the goal of the legislation should be to make future reforms easier, to make future reforms more likely.

So I wonder, a. do you see anything in the IRA that qualifies as kind of that like an eye on infrastructure building?

Hahrie Han

Right.

David Roberts

And if not, what would you like to see, like, in future legislation? What are the sorts of things you might put in legislation that would help this infrastructure building?

Hahrie Han

Yeah. I think it's so important in designing policy to think about what the feedback effects that you're creating, because a lot of the most effective policies that we've seen throughout history are ones that have these feedback effects that essentially what you want to do is create a feedback effect that strengthens the constituencies that you want to strengthen and then either weakens or divides the opponents to the bill, right. And that's how you create the kind of loops that you're talking about that enable the passage of the next set of reforms, make them even more likely than they were before with the IRA.

I think the opportunity that's on the table is the fact that so much of this money is essentially being delegated out through state agencies and other local governmental agencies that are operating at many different levels of government. And the extent to which this money can be doled out in a way that builds what I like to think of as relational state capacity, right. The ability of these governments to co govern and work in partnership with community leaders and community groups on the ground that only then makes the next generation of reform and policy and funding and implementation that much stronger.

And so I feel like a lot of the design questions that we have on the table right now about how this money gets allocated through this network of state and local agencies and other intermediaries is going to be really important in helping determine the extent to which we have those kind of feedback loops or not.

David Roberts

Yeah. And something I've actually heard from people in the back rooms involved in building IRA is that among Democrats in Congress, there's been a learning, let's say, that you don't necessarily want to channel all your money through state governments, right. Because there are a lot of perverse state governments who will do things like refusing billions of dollars of free. Federal money so that they can keep their poor people from having health care, that kind of thing, right. Like they've learned from the past that you can't rely on. So a lot of the IRA is sort of built around the idea of going straight to communities, straight to local communities, which I thought is heartening that the Democratic establishment is learning things.

Hahrie Han

Right, yeah. And it's heartening, partly because it's learning how to play that political game, right. But also heartening because then that implicitly builds this capacity and these capabilities in these local communities in a way that can have greater effects down the road.

David Beckman

Yeah. And if I could just add to that, just to connect something we've been talking about. So what does it look like to make a grant on movement infrastructure? A couple of the grants that Mosaic is making this year focus on a really bridging network of 17,000 plus climate advocates, policymakers, academics. It's just connecting that group. Another grant is facilitating rural implementation and trying to create networks that make it easier for folks who may not be as commonly working in the areas of electrification and tax incentives and so forth to pry those opportunities. And there's another grant that's actually focused on government officials themselves and educating them about the opportunity, not in environmental terms, even necessarily, but in terms of what they can do for their communities.

So those are ways of sort of spurring the kind of relationships that Hahrie is talking about.

David Roberts

From where you're sitting here. So you got a bird's eye view of dozens and dozens and dozens of small groups who want money. So I wonder part of shifting funding from a couple of big groups to a wide variety of small groups is about just sort of like hedging your bets and building infrastructure. But I wonder if you found among the applicants just ideas and strategies that are not represented among the big groups. In other words, like genuinely new ideas for how to approach things. I wonder if you could just talk about some of the applications and the patterns that emerged.

David Beckman

Well, one of the things that's amazing is that it's such a diverse set of ideas. And from a philanthropic practice perspective, when you're not relying on a single individual to vet potential proposals, I mean, nobody knows everybody, and everybody's got a limit to their day. You just get an eye-opening kind of response. And I think that was something that everybody CEOs of big groups are part of Mosaic CEOs of smaller groups, EJ groups, felt. So some of what we saw is a desire to sort of shift the terms of debate. And I don't know how that, I don't think, is very well-funded in mainstream environmental philanthropy.

Different theories of change, different approaches to the economy, questions around how to frame economic growth in different ways, indigenous perspectives on the protection of the environment and elevating the rights of nature. As a theory, these are not directly related to a tax incentive for decarbonizing your house, but they come through and they're interesting perspectives that don't get a lot of play. More practically, we saw a lot of really interesting collaborations between different organizations, some of which work together, some of which don't, and are using the opportunity to apply for a collaborative grant to stretch their wings in ways which, as Hahrie saying, may grow into something that has nothing to do with the proposal before us. One interesting proposal was to build solar capacity in communities of color using the tax incentives and actually, I think, direct grants that are available for solar installation, not only generally, but in underserved communities to turn that into a workforce development effort for brown and black people.

So there's a whole set of things that I think are going to be helpful in actually reaching the goals of the IRA which are not guaranteed to happen and can build for the future.

David Roberts

One other question I wanted to ask in terms of what was on your mind as you're picking grantees is, and this is anyone who listens to the pod will know that this is an enduring obsession of mine. But it seems like one of the basic headwinds facing implementation of the IRA, facing basically any progressive effort, is this massive, extremely well developed propaganda apparatus on the other side that has basically captured rural America, has almost entirely captured rural America. And in a sense, like any attempt to do anything reality based in the face of that just gets swamped. So I wonder if there were a lot of ideas among the applicants about, to put it dramatically, information warfare about how to fight back against what is the inevitable tide of misinformation about this bill, about these technologies, et cetera, et cetera. Was that a theme?

David Beckman

Yes, but maybe in a more positive sense that the IRA, I think to the credit of its designers, is itself a pretty profound attempt to push back on that narrative. But because really what we're talking about is decarbonization in theory, but the practice of it is through electrification of power and cars and incentives for clean energy and right down to what any of us, as people who live in a home could get a credit or a refund for purchasing like a heat pump. And there is, in the IRA, specific money that goes both to vulnerable communities, EJ communities, as well as to rural communities, which there are 40 million people in the US who live in rural communities, 50% of the land mass of the country.

And so we're talking about a significant space in the country and a lot of people. The opportunity, for example, to decarbonize rural electrical cooperatives which have really relied on coal, which has very significant public health impacts, in addition, is a huge opportunity that isn't necessarily cloaked in environmental terms. It's a great opportunity to reduce cost and to create jobs. And there's a whole set of parts of the IRA that are entirely focused on farm communities and forest communities that involve credits and other types of incentives for regenerative agriculture, for dealing with water scarcity, increasing water scarcity, and things that just have basic bottom line benefits economically and are part of cleaning up and making the economy greener in those areas.

So I see those set asides, or those components, set asides is probably not the right word, for environmental justice and for rural communities as a really powerful step. And I think it connects a lot to what Hahrie is talking about in terms of will this change the experience of people who might think of environmental groups as not their friend and really recontextualize what this is about.

Hahrie Han

And if I can chime in here just on the question of disinformation that is spreading in so many of our communities and especially in a lot of these rural communities. I've been doing a lot of work recently studying evangelical communities which operate in a variety of different kinds of contexts. But one of the things I've really learned from the way a lot of evangelical churches organize their communities is they have this idea that belonging comes before belief. That so often, I think, when we think about building an environmental movement, there's sort of this implicit assumption that belief comes before belonging, right?

Like that you've got to sign on to this idea that we all need to decarbonize before we're going to invite you into our meetings. And if you show up in your Range Rover and your hunting gear, maybe you're not going to feel as welcome as you do otherwise. And these churches have the very opposite idea where they say, look, you don't have to believe in God. You don't have to believe in any God, and especially our God. We're not going to be shy about what we stand for, but you're a part of us no matter what.

And they have this attitude of radical hospitality. And that's really undergirded by a lot of research that we have on disinformation, where when you're trying to combat that kind of propaganda, the least effective thing you can do is throw a lot of scientific evidence at someone who ...

David Roberts

Fact sheets.

Hahrie Han

Right. But the best thing that you can do is have someone who they trust, with whom they feel this sense of belonging, come and talk to them and present an alternative narrative. And so, in that sense, I feel like a lot of the work that Mosaic is doing in investing in these community based organizations that can build those communities of belonging in rural areas across America is another really important piece of combating this kind of disinformation.

David Roberts

Yeah, I think that's such an important point. I mean, you have results that support this basic conclusion from sociology, from neurology, name your field. It all is coming together to basically show that social relationships are primary and very often your beliefs are derived from those rather than vice versa, as you're saying. This is also a long-time criticism of the left and this is sort of conventional wisdom at this point. Unions were sort of the left's tool. Unions and liberal churches were the left's tool for doing that, just for literally bringing people together in the same room so they can see and smell one another and share beers.

And that stuff is so important. And unions have withered notoriously and liberal churches have kind of withered and the left has nothing to replace them. So in that sense, I think it's just great to be funding these super basic, just like get in a room together, group type things.

David Beckman

And if I could just say, one of the challenges practically with the Hahrie's talking about radical hospitality is that let's just say that the federal government doesn't come with radical hospitality even if it's offering billions of dollars that can be used. So breaking that down, how do you apply for money? How do you even track? I'm a lawyer. I have difficulty with the Federal Register and I was trained and supposedly I'm supposed to be competent in that. And a lot of the investments that we're making and others I think hopefully will be too, is about creating some basic kind of open doorways that make the opportunities accessible and relatable when they are not, in any of our lives necessarily top of mind.

We're also supporting faith communities through Mosaic and veterans who are trying to organize around climate change and other new or newer voices, nurses and healthcare professionals who I think reflect some of the experience and the research that Hahrie is talking about where it's a lot better to have somebody who you trust, who is in relationship with you, talk to you about an issue that you might not hear. The same if it's sort of an environmental leader on television or something like that.

David Roberts

Yeah. And this is to Hahrie's earlier point. Once that relationship is established, it works for the next thing too, right?

David Beckman

Yeah.

David Roberts

That's, I guess, what we mean by infrastructure. Like, once it's there, it's built and it operates beyond the immediate context. Hahrie, I wonder one sort of question I had is a lot of the money in the IRA is just for very practical, prosaic stuff machines, retrofits, whatever. And so most of the attention around all this is sort of building these networks, building this infrastructure to allow people to access that money. But I wonder if you've given any thought or David, I'd be interested to hear your thoughts on this too, is whether the money itself can be spent in such a way as to serve this goal.

Spent in such a way as to encourage infrastructure. You know, not only sort of trying to get the money, but trying to direct the money in ways that are reinforcing of this larger goal.

Hahrie Han

You know, one thing that I think about is this question of what are the mechanisms of accountability that are being created through the way the IRA gets deployed? Because ultimately that question of accountability is the one that's going to determine the extent to which these ongoing feedback loops are created in the ways that would favor ongoing reform or not. And so as all this money is being deployed for heat pumps or other basic machines that are needed to help decarbonize the entire economy, I think it's not just about spending that money once, right, but it's about restructuring the way the economy works in these certain kind of communities. And how can that be done in a way that will continue to ensure that the kinds of voices that we want at the table are continually there and that those voices are strengthened through the development of this whole new system?

David Beckman

Yeah, two thoughts on that. One, that a very kind of visual thing came to mind because there's a part of the IRA that is focused on environmental justice and on transportation projects in the that literally physically split communities, usually Brown or Black communities. And the opportunity actually to reconnect is quite a beautiful visual metaphor for what you're asking about and I think would almost naturally create the opportunities for communities to rediscover their connections in ways that have been literally physically severed by decisions. But beyond that, and more broadly, I think this is where advocates activists come into play because I think a couple of possibilities are out there.

One is that the IRA is successful, but the experience of individuals and even companies is very solitary. I go to Home Depot, I get something from my house that costs less, or I can fill out a form and get a rebate check from somebody. That's a solitary experience. It may be very marginal in terms of anybody's psychological thinking about these issues, but if environmental organizations or those that are interested in these issues are able to surround those sorts of economic activities with new connection opportunities, information that as Hahrie says it is relatable where trusted messengers are delivering it.

So that act of participating in the IRA's opportunities is also an act of stepping forward and opening yourself up to, well, you know what? That heat pump actually performs better than what I had before. Maybe some of these environmental ideas aren't so crazy. That's where you get chess not checkers. And that's so essential that activists and advocates working on climate really seize this opportunity to work dimensionally around these opportunities. Because if they don't, I think we could have a different level of success, but not something that would be as systemically transformational as is possible.

David Roberts

Right, yeah, I think about the analogy in fitness or weight loss, one of the sort of most common forms of advice now is find a group or a community or even just another person and make your goals public like put your goals out there and then be sort of accountable to that other person. Or I think about the conversation about game-ifying things. Just sort of like make things that are solitary social in some way, where you get social reward or social feedback or you have social accountability. A., that's good for you to have those networks, but also, like, you're just more likely to do those individual things if you have some social network that they're involved in.

And your answer made me think of how you would think about doing that with IRA, right? Like somehow making the act of going to get your heat pump social in some ways so that it brings some feedback or accountability or so it weaves you more into some sort of group setting.

David Beckman

Right, that's the play. That's the thing to do. And that can make a huge difference. Ask can organizing around money that is not actually available to individuals but is going to so many parts of the economy that impact people directly? Like ports, there's $3 billion for ports and $3 billion for reconnecting communities, I mentioned that a minute ago. And on and on. And that involves influencing government actors, as Hahrie was pointing out earlier, both to take advantage of the opportunities and then to do so well to propose projects that are going to make a difference. That's a classic organizing opportunity.

David Roberts

And of course, if you have the infrastructure in place, you can reward politicians who do the good thing, thereby showing the other politicians that there's positive feedback to be had in this direction.

David Beckman

Yeah.

David Roberts

David, one more question for you, which is slightly prosaic, but I have been thinking about it a lot, which is just this sort of initial round of throwing open the gates of environmental philanthropy money to this much wider variety of participants, smaller groups, et cetera, et cetera. In a sense, the initial rush of it is like a sugar high. Like it's great, I think everybody's excited. But over time you do need the foundation's obsession with metrics and accountability, I think we can all agree, has maybe sometimes gone overboard and results in a lot of paperwork and a lot of unnecessary difficulty and gatekeeping.

But those needs are not made up, right? So are there any sort of performance metrics or what does accountability look like when you're moving into this kind of fuzzier relational stuff? What would it take for a grantee to lose their funding? What do you have in place in terms of accountability? Or have you thought about that a lot?

David Beckman

Well, it's a good question and it's a question, I think that people in philanthropy and people who are looking for money think about a lot. The baselines, I think, are important, what's the context in which we're operating and a lot of the there's kind of basic due diligence that an organization is a 501(c)(3) and so forth and so on. But beyond that, whether it's a Mosaic context or a more traditional foundation. A lot of the metrics are artificially simplified, and they become, at times, bean counting operations. And I know this because I used to propose those to foundations when I was doing advocacy.

David Roberts

It's easier, right? I mean, one of the things about it, it's very easy if you have a simple marker.

David Beckman

Right, I'm going to write a report, and then I can send the report to the funder and say, look, I wrote a report, and if I'm lucky, I got on David's podcast, so I got brought attention to it. And I'm not suggesting that those things don't make a difference. I used to write reports, and I think they can make a difference in the right circumstances. So the question becomes, what are we comparing to? And I think where we are right now is sort of a bit of an artifice. Having said that, you can evaluate and learn from movement building just as you can grants, just as you can from any other.

You just need a much more relational touch. And I would ask Hahrie might want to jump in on this because she's looked so carefully at the types of outcomes that occur. And I think the outcomes that we're looking for, we're looking to be patient funding. We're looking to recognize that we're not going to necessarily see some sort of vivid and tangible, like ribbon cutting, in a year, and that we're not really asking people to propose things to us which we know as a collective. Making decisions from the advocacy community, from the field, are simply unrealistic. So I think one of the most important things to do is to recognize that if we're going to build resilient organizations, that that in itself is the outcome we're looking for, as opposed to some sort of simplified, kind of artificially linear, kind of gantt chart that we can say was met or wasn't met.

Hahrie Han

I totally agree with what David was saying. And an analogy that I use sometimes in thinking about this is the idea that in the corporate world, in the for-profit world, we invest in companies all the time based on their assets, right? And that I would be foolish, in fact, as an investor, if I only evaluated a company's profits in the prior year and didn't look at their assets going forward, that I should, in fact, be really making judgments based on what they can do in the future. And I think in the same way, for movements, a lot of philanthropy, I think, tend to only hold movements accountable for the equivalent of their, quote unquote "profits."

But really, what they should be investing in is what those assets are going forward. And I think one of the things that's really exciting about what Mosaic is doing is trying to strengthen those assets and then continually invest in them over time.

David Beckman

Yeah. One, just as a quick vignette, we've been doing this only a couple of years but it's long enough now to start hearing from grantees who themselves report in excited tones how amazing it is from their perspective to be able to get funding for things that would simply not even be possible in other contexts. And what it means if you're a small hub for advocacy in appalachia to have some communications money or to have some of the things that maybe the larger organizations just take for granted. And we're going to be developing a lot of that information because I think you're onto something, David.

That mainstream philanthropy. To move hundreds of millions and billions in these directions is what we need to do. And that we're not going to be able entirely to tell people just to trust us, that we have to meet folks where they are and focus on developing sort of a comfort and a conversance with what we're attempting to do here.

David Roberts

What about and I guess I throw this one to both of you too. We're so behind the eight ball on climate change and a lot of other environmental problems that a lot of solutions are relatively obvious. Like, a lot of the things that need to be done are relatively obvious and uncontroversial. But you can sort of imagine different demographics coming at this from different places having some pretty fundamental disagreements about the theory of change or even sort of what kind of society we're shooting for. There's sort of a climate socialist left and then there's like a very sort of establishment center-left kind of big environmental group.

And there are real philosophical and ideological disagreements. And I wonder just how do you deal with those when they can we find enough in common that they can be kind of papered over and we can move forward together? Or do you worry about those emerging in a more enduring way?

David Beckman

Well, I mean, as you know, David and Hahrie those cleavages have already emerged in enviornmental advocacy. And I think we're in the midst of a reckoning about how larger organizations have operated, how big philanthropy operates the role of a just transition versus simply looking for tons of reduction. Part of Mosaic's, kind of, birth came not from me but from 18 months of really cogentive development with 100 different leaders that really looked at those questions. I think as much as infrastructure is important intangible ways as Hahrie is emphasizing, the relational components are essential. And they don't resolve every question whether you're in business or you're in sports or whatever you're doing in life, your own relationships.

The fundamental question isn't whether people can truly agree on every last detail. It's whether they can form more productive relationships in the advocacy work they're doing. That's the goal. And if you can make an advocacy community of 15,000 organizations like 10% better that is a net effective investment that's huge in terms of its outcome. So we're having these conversations as part of Mosaic and they're going on across the field. And the question is, where do you build the infrastructure to have them in ways that are reperative? One of the focuses of Mosaic is about relationships and trust.

And some people look at that when we show a PowerPoint. They're like relationships and trust. What does that have to do with the environment or climate? Well, actually ...

David Roberts

It has everything has everything to do with everything.

David Beckman

That's right. But it's not a commonly you can look at a lot of foundation websites before you're going to find relationships and trust.

Hahrie Han

Difference and disagreement is inherent to any kind of collaborative effort, especially one at the scale, though, that we're talking about. And I think the idea that we're going to be able to either paper over or ignore those differences or get everyone to just get along sometimes feels like it's a frustrating way to approach the problem. And what we know from a lot of previous experiences and research and so on, is that what makes it possible for these kind of coalitions to navigate those kind of deep strategic differences like the ones you're describing about? Is the extent to which they create equitable power sharing agreements so that the super left-y groups and the center-left groups can kind of have the sense that we know we're not going to all agree on everything in the end, but we're going to be really clear about how we're going to make decisions together, about what we're going to do and how we're going to allocate resources.

David Roberts

We're going to be heard, right. So often it's just about that as much as anything else.

Hahrie Han

Right, and so having a participatory board where there's this transparent governance process just kind of starts to create those habits of learning how to share power across lots of different theories of change.

David Roberts

I think that working together in person or like face to face often shows people that despite our differences, there is actually a time we can work together on there and we do have more in common than we thought. Whereas the common communicative environment these days of social media is more or less structured to have the opposite effect, right, to sort of exaggerate differences and to encourage people to dig in and be the most extreme version of their selves. So anything that works against that is a social good in my book.

Hahrie Han

Yeah. I think that sometimes we mistake attention for power. And part of why social media can be so alluring is because it gets you lots of attention and the more divisive you are, the more attention you get. But to actually build power, you have to build those kind of bridges. And so what we have to do is kind of break that idea that having more attention is necessarily the same as having power.

David Beckman

Yeah. And I'll just say quickly that Mosaic launched into the teeth of the pandemic and we've made far more progress when we were able to actually meet together. It's a very different thing to look at somebody through. Effectively, whether it's your handheld screen or a screen on your desk, tends to reinforce the sort of archness that people can bring into a room where there are diverse perspectives, but there's nothing like the in-person meetings and even the socialization between people who don't know each other just to create a little bit of grace between them.

David Roberts

A final question that I'd like to hear you both weigh on, which is very general, but just this shift in approach that Mosaic sort of represents, of focusing on movement infrastructure, focusing on relationships and just sort of infrastructure building and having a much more diverse, pluralistic decision making structure, sharing power, all this kind of stuff. Very much for reasons we've discussed. Tax against a lot of the sort of trends and tendencies on the left in the past few decades. What's the theory of change here? What would you like to see if this catches on? Like, you know, in a positive world where this new strategy catches on?

What would you like to see in, like, five to ten years? What can you imagine improving? What is the sort of theory of change here if this new approach takes over? What do you think is possible in the next five to ten years?

Hahrie Han

My mind goes back to the point that you were making, David, earlier, which is that there's been this long standing pattern where it feels like the right invests in the kind of deep work that is needed to make large scale shifts in society and politics. And the left feels like it's swimming along in the shallow end all along the way. And we're in a moment right now where clearly the change that we need is deep and not shallow, and it's got to operate quickly and also in the long term. And so for me, it's like when you build this kind of infrastructure and mechanisms like Mosaic, what I would love to see in five years, ten years, is a kind of deepening of the movements and the network of organizations that are able to continually advance the kind of agenda that we really need.

And so you can think back to the early decades of the rise of a lot of the kind of organizations that comprise the right. They sort of started at the same place that we are now, in a way, and steadily built over a couple of decades. That kind of death that is now being deployed.

David Beckman

Yeah. And I'll just build on that. I think, from a very practical sense, the conversation we're having today is about profound existential challenges that we're facing with climate change and beyond. I hold, as somebody who's devoted my professional life to this, both real pride in our grantees and the work that's being done. Where would we be without the laws that we've got and the work that's. Been done. And at the same time, this recognition that so many have that notwithstanding our best efforts, that those efforts aren't adding up to keep pace with the scale of the change that we're facing.

And so, very practically, Mosaic and things like it, if it can be a model, is designed to create a more powerful and effective environmental movement that can effectuate the big change that we need. Not just theorize about it, not just plan for it, not just write about it, but actually implement it at scale and over the time period that's available to us, which, with climate, is not that long, by 2030. That's what we need to be focused on, and that's what Mosaic and things like we've been talking about today are really directed toward.

David Roberts

A positive note to wrap up on. Hahrie Han, David Beckman, thank you so much for coming on and talking through all this stuff, and good luck with your efforts.

David Beckman

Thanks so much.

Hahrie Han

Thank you for having me.

David Roberts

Thank you for listening to the Volts podcast. It is ad-free, powered entirely by listeners like you. If you value conversations like this, please consider becoming a paid Volts subscriber at volts.wtf. Yes, that's volts.wtf, so that I can continue doing this work. Thank you so much, and I'll see you next time.

This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.volts.wtf/subscribe

More Episodes

2026-02-18

2026-02-18

2026-02-11

2026-02-11

2026-02-06

2026-02-06

2026-02-04

2026-02-04

2026-01-30

2026-01-30

2026-01-09

2026-01-09

2025-12-17

2025-12-17

2025-12-12

2025-12-12

2025-11-28

2025-11-28

2025-11-26

2025-11-26

2025-11-21

2025-11-21

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2026 Podbean.com