The Coffee Klatch with Robert Reich

News:Politics

The most important protector of workers' rights you've never heard of

2022-10-06

2022-10-06

Gallup reports that a whopping (and record) 72 percent of Americans between the ages of 18 and 34 approve of labor unions. That’s especially remarkable given that a bare 3 percent of Americans between the ages of 18 and 34 belong to one.

Despite the recent victories of Starbucks workers and noteworthy efforts by Amazon warehouse workers, the rate of union membership in America has fallen to its lowest in seventy years: now a bare 6 percent of private-sector employees.

Republicans hate unions. Democrats won’t abolish the filibuster, so lack the votes to strengthen unions. (With any luck, that will change in the next Congress.)

Yet there’s a direct and unambiguous relationship between the rate of union membership and the share of total income going to the top 10 percent, as this graph makes clear:

The fortunes of American unions and workers are starting to look up nonetheless— and that’s mainly because of a person you probably never heard of, in the most important job you probably didn’t know existed.

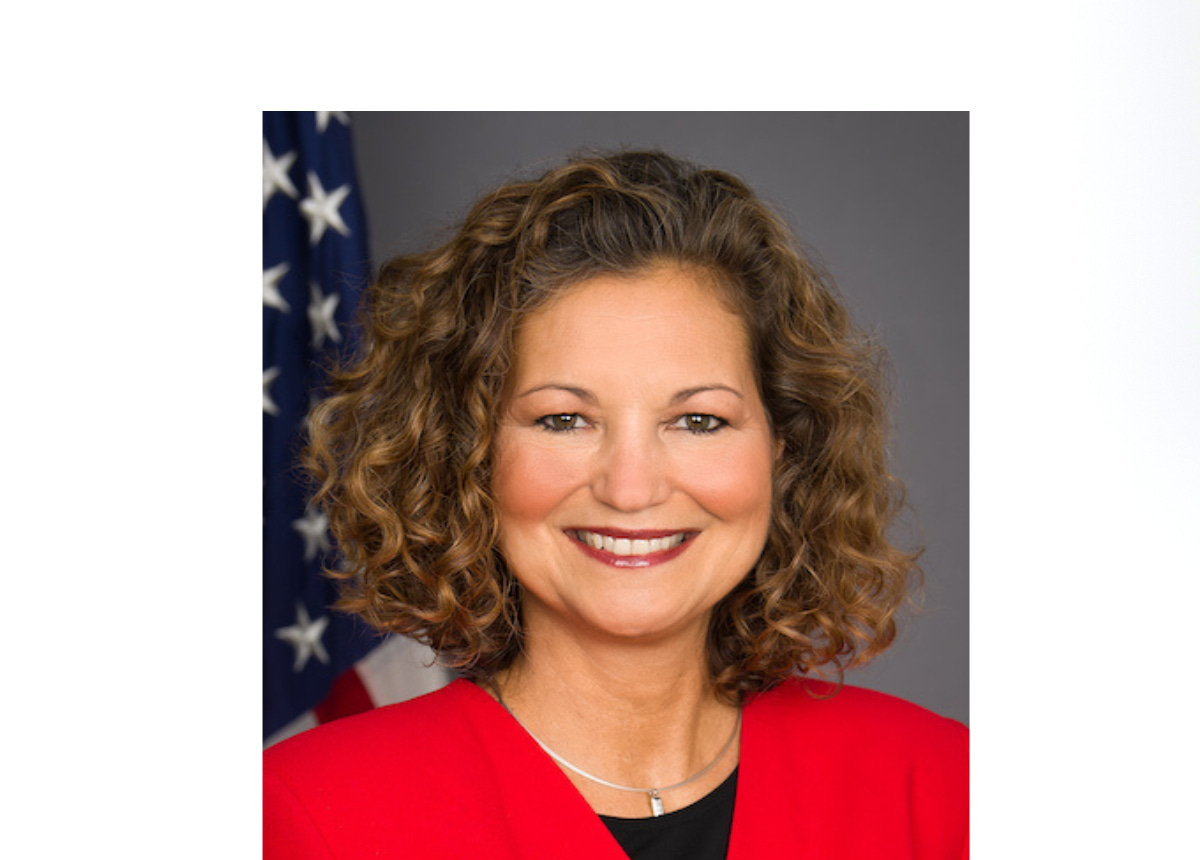

Her name is Jennifer Abruzzo. A year ago she was confirmed on a party-line vote to be general counsel of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB).

The NLRB hears cases, makes rulings, and sets binding precedents about what does and doesn’t constitute a violation of America’s labor laws.

Its general counsel is the agency’s chief prosecutor, directing roughly 500 attorneys across the nation in 26 regional offices.

Which gives Abruzzo a huge say over how the private sector in America may or may not treat workers.

Installing Jennifer Abruzzo as the NLRB’s general counsel may be the single most important initiative the Biden administration has taken for working people so far — and least known.

Abruzzo is no newcomer to the agency. She spent 23 of her 58 years as an attorney there, starting as a field attorney in Miami and rising to deputy general counsel during the Obama administration.

But she has taken her new job by storm, instructing her 500 attorneys to make it far more costly for employers to illegally fire workers for trying to form unions.

It’s about time. American companies have been charged with violating federal law in over 40 percent of all union election campaigns. But until Abruzzo came on the job, the worst that could happen to them was the equivalent of a weak slap on the wrist.

Starbucks, for example, has illegally fired dozens of employees for trying to organize a union. Abruzzo has responded with complaints accusing Starbucks of 81 illegal labor practices — including those firings, plus spying on workers and closing stores in retaliation for unionizing.

(The Starbucks workers’ union also wants her to file a complaint against the company for giving raises and improved benefits to baristas at non-union stores but not to workers at stores that have already unionized. Hopefully, she will; it’s also blatantly illegal.)

Apple has been telling workers at its retail stores that joining a union could result in fewer promotions and inflexible hours. The National Labor Relations Board just issued a complaint against Apple over accusations that it interrogated its retail workers about their union support and prevented pro-labor flyers in a store break room.

Rather than give employers such as Starbucks and Apple mere slaps on wrists, Abruzzo is seeking to increase worker power overall, in seven important ways:

* Getting workers who have been illegally fired back into their jobs right away, while their organizing campaigns are still ongoing. She is getting courts to compel this (by injunction) by arguing that waiting for the legal process to unfold will be too late.

* Getting back pay for these workers that covers financial losses as well as lost wages — including their withdrawals from savings and retirement funds, loans, and credit card fees. And she wants employers to compensate unions for expenses incurred in fighting their illegal behavior.

* Making it illegal for employers to require that workers attend “captive audience” meetings to hear management’s case against unionizing. (The union seeking to organize Amazon’s warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama, has alleged that Amazon is doing just this.)

* Making employers recognize a union once a majority of workers sign cards saying they want one (thereby returning to a 1949 NLRB rule). “We should not be allowing those employers to delay recognition so that they can coerce these workers to think differently or choose differently,” she says.

* Making it illegal for employers to misclassify workers as independent contractors — which the Board can remedy by finding that the workers are employees and thus eligible to unionize. (On March 17th, NLRB attorneys filed a complaint against a port trucking company at the Los Angeles harbor for illegally misclassifying drivers. If upheld, the firm will have to compensate the drivers for lost wages and expenses and provide a union access to the drivers for an organizing campaign.)

* Allowing graduate students and college athletes to unionize.

* Recommitting the NLRB to protect the right of immigrants to organize regardless of their immigration status.

Abruzzo can’t make any of this happen by waving a wand. She and her 500 attorneys must first win cases before administrative law judges, and then the NLRB.

These cases are underway. With a Democratic majority on the NLRB, there’s a good chance she’ll prevail there. Yet many companies that lose will appeal the NLRB’s decisions to the federal courts. A few of these cases will end up at what’s become a viciously anti-labor Supreme Court. But it normally takes years for NLRB rulings to reach the highest court, by which time workers may have gained a real voice for the first time decades.

As Harold Meyerson has reported, a new generation of 20- and 30-somethings are organizing at warehouses (Amazon Labor Union leader Chris Smalls is 34), at retail and food outlets ranging from REI and Starbucks to Chipotle and Trader Joe’s, and even at nonprofits, museums, state legislatures, and universities.

If they succeed, Jennifer Abruzzo will deserve much of the credit.

“We are a neutral, independent federal agency, but we have a pro-worker congressional mandate, and I’m going to vigorously protect the right of workers to self-organize, join a union and bargain collectively with representatives of their own choosing.” Abruzzo says.

She’s on her way to doing this, folks.

More power to her — which means more power for American workers to countervail the immense power of big American corporations.

P.S. Thank you for being part of this community. Subscribers to this newsletter are keeping it going. Please consider joining if you haven’t already. We also appreciate you sharing this content with others and adding your thoughts in the comments.

This is a public episode. If you’d like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit robertreich.substack.com/subscribe

More Episodes

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2024 Podbean.com