The Coffee Klatch with Robert Reich

News:Politics

Are record levels of stress inside us — or outside us?

2022-09-27

2022-09-27

Last week, a panel of medical experts recommended for the first time that doctors screen all adult patients under 65 for anxiety disorders. The advisory group, called the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, said the guidance was intended to help prevent mental health disorders from going undetected and untreated for years or even decades. It made a similar recommendation for children and teenagers earlier this year.

Appointed by an arm of the federal Department of Health and Human Services, the panel has been preparing the guidance since before the pandemic. Its recommendation highlights the extraordinary stress levels that have plagued the United States in recent years. Lori Pbert, a clinical psychologist and professor at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, who serves on the task force, calls mental health disorders “a crisis in this country.”

What’s the answer to this extraordinary rise in stress, anxiety, and depression?

Some say we need more psychiatrists, psychologists, and therapists.

America is “short on mental health resources on all levels,” says Dr. Jeffrey Staab, a psychiatrist and chair of the department of psychiatry and psychology at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

But … wait.

Maybe what people feel are valid descriptions of personal experience rather than symptoms of mental illness. Maybe we need to stop thinking about anxiety and depression as “disorders” and start regarding them as rational responses to a society that’s become ever more gruesomely disordered.

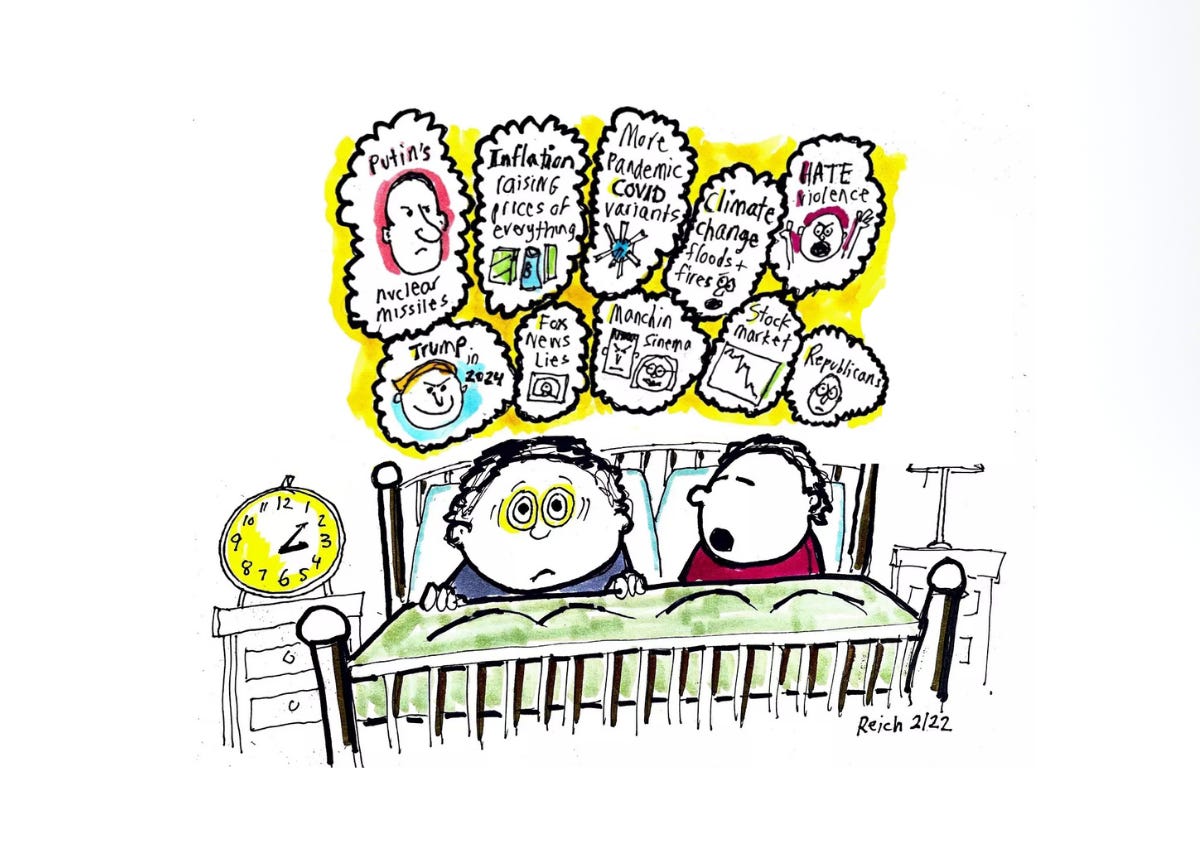

Who has not feared illness and loss of loved ones from Covid-19? Who isn’t concerned by the soaring costs of living and the growing insecurity of jobs and incomes? Who isn’t terrified by Trump’s and his followers’ attacks on democracy? Who doesn’t worry about mass shootings at their children’s or grandchildren’s schools? Who isn’t affected by the climate crisis?

Add in increasingly brutal racism; attacks on Asian-Americans, Hispanic-Americans, and Jews; mounting misogyny and anti-abortion laws; homophobia and transphobia; and the growing coarseness and ugliness of what we see and read in social media — and you’d be nuts if you weren’t stressed.

Studies show that women have nearly double the risk of depression as men. Black people also have higher stress levels — from 2014 to 2019, the suicide rate among Black Americans increased by 30 percent.

Are women and Black people suffering from a “disorder,” or are they responding to reality? Or both?

White men without college degrees are particularly vulnerable to “deaths of despair” from suicide, overdoses, and alcoholic liver diseases, with contributions from the cardiovascular effects of rising obesity, according to the American Council on Science and Health.

Are they suffering from a “disorder,” or are they responding to a fundamental change in American society? Or both?

In their book, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, economists Anne Case and Angus Deaton argue that “the deaths of despair among whites would not have happened, or would not have been so severe, without the destruction of the white working class….” Part of the problem, they say, is that the less educated are often underpaid and disrespected, “and may feel that the system is rigged against them.”

Even if we had far more mental health professionals, what would they do against these formidable foes? Prescribe more pills? If anything, Americans are already overprescribed.

I’m not arguing against better access to mental health care. In fact, quite the opposite. Increased staffing and improved access to care are very much needed.

(Right now over 2,000 mental health therapists, psychologists, and social workers in California are entering their second month of an open-ended strike to make Kaiser Permanente, the nation’s largest nonprofit HMO, to improve access to care for its patients. The outcome will have nationwide ramifications for determining whether laws that guarantee parity for mental health care will, in practice, help patients access care that meet their needs.)

But in addition to providing more and better access to mental health care, we must also try to make our society healthier…

… So that the next pandemic doesn’t kill a larger percentage of Americans than in any other advanced nation.

… So that Americans have more job security and stronger safety nets, rather than the least economic security of any advanced nation.

… So income and wealth aren’t the most unequal of any other advanced nation.

… So our democracy survives Trumpism and big money.

… So guns and assault weapons are difficult to buy, rather than easier to get than in any other advanced nation.

… So we take a leading role in ending the climate crisis.

… And we do everything possible to overcome racism, homophobia, and misogyny.

These goals are terribly difficult to achieve, of course. But without seeking to achieve them — without making their achievement central to what we must do as a people — no number of psychiatrists, psychologists, and therapists, and no amount of medications, will be enough to substantially reduce the stress, anxiety, and depression so many Americans are now experiencing.

This is a public episode. If you’d like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit robertreich.substack.com/subscribe

More Episodes

2022-09-17

2022-09-17

2022-09-16

2022-09-16

2022-09-12

2022-09-12

2022-09-09

2022-09-09

2022-09-01

2022-09-01

2022-08-30

2022-08-30

2022-08-29

2022-08-29

2022-08-26

2022-08-26

2022-08-25

2022-08-25

2022-08-23

2022-08-23

2022-08-19

2022-08-19

2022-08-18

2022-08-18

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2024 Podbean.com