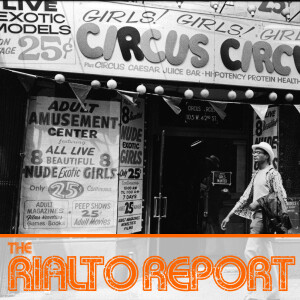

Cop Porn: When the NYPD made a Porn Film – Part 1 – Podcast 130

2023-07-30

2023-07-30

In 1970s New York, hardcore sex films and adult bookstores raged across Times Square like a forest fire. It was great for the sex business, but it also depressed tourism and commerce, and emboldened organized crime in an already deeply beleaguered city.

The cops fought back, busting theaters and sex shops on a regular basis. It had little effect: most of the sex operators just paid the fixed fine and re-opened the next day with no further consequences. For a police force already laid low by the city’s financial crisis, it was a demoralizing and losing battle.

And so, in 1977, the Public Morals Squad, a division of the New York Police Department, came up with a novel idea: what if they set up an undercover porn production company and pretend to make their own adult movies so that they could infiltrate the shadowy alliances that connected the pornographic movie theaters to the mob-controlled film distributors?

What resulted was a law enforcement operation that was as unprecedented as it was brash and secret. Secret that is, until the story leaked to the press, and a nationwide scandal erupted.

Over the last ten years, The Rialto Report wanted to know more about this unusual police operation. I tracked down many of those involved – from all sides of the story – to establish what actually happened. We’re going to focus on three characters: Phil Russo, the cop who set up the undercover company to tackle the sex industry. Michelle Lake, the inexperienced adult film performer at the heart of the story. And Varla Romano, an NYPD detective who worked on the case. As for the rest, most names have been changed to protect the innocent – and the guilty.

This is the inside, untold story of Cop Porn.

————————————————————————————–

When Michelle Lake slept, she dreamed of being weightless. She floated in clear, azure oceans, the warm water embracing her, washing away her anxiety and fear. She was surrounded by dolphins – kind-eyed, smooth-skinned, and accepting. They circled her silently, and she felt safe in their presence. She smiled back at them. But when Michelle woke, the dolphins disappeared, and her heart sank back down into her chest with blunt dread. She faced reality with unease.

When Phil Russo slept, he too was haunted by mysterious creatures that lived beneath the surface. But these were different beasts. Phil’s dreams were of mole people: society’s rejects that inhabited the dark, labyrinthine passages in the subway beneath the streets of New York City. They scavenged and stole to survive, rarely venturing above ground, their faces caked in grime. In sleep, as in life, Phil was a cop, patrolling the tunnels looking for lawbreakers. Sometimes he found them. Sometimes they found him. Phil usually saw the whites of their eyes first, a split second before they attacked, pummeling him to the ground beneath a blur of blows. He woke in a cold sweat, before relief slowly washed over him. He faced reality with foreboding.

Dolphins and subterranean dwellers. The complexities of life often reside beneath the surface.

*

August 1977. A hotel room at JFK Airport, New York.

Apart from their recurring dreams, Michelle and Phil had little in common. They were from different backgrounds and generations. But at this moment, they were standing face-to-face in a beige airport hotel room.

Michelle was in her early 20s, attractive, and fresh-faced. She was nude, dripping with pheromonal sweat. She smiled with a glow that betrayed the energetic sex she’s just performed with a faceless young buck still stretched out on the bed behind her, casually lighting a cigarette.

Phil was a long decade older. He was perspiring too, but his glow was caused by stress. He vainly tried to mask his discomfort at what he’d just witnessed by pretending to focus on a distant object far out the window. His heart beat urgently against the NYPD badge hidden inside his jacket pocket. His standard-issue Smith & Wesson remained nestled at the bottom of a duffle bag at the foot of the bed. There is a quiet feeling in the hotel room but Phil’s psyche had been rudely disrupted. He was accustomed to seeing drug dealers with their brains splashed across Eighth Avenue, or teenage hookers manipulated by fur-clad pimps – but this scene is a whole different kind of strange.

Phil grabbed a towel and handed it clumsily to Michelle. She thanked him, but he still couldn’t bring himself to make eye contact with her, let alone talk. At least not just yet. When she’d finishing toweling her body, he reached into his pocket and handed her $150. Michelle took the money, though in the moment, nude and perspiring, she didn’t have a clue where she was going to put it.

There weren’t many other people in the room. Two of them were concealing their disquiet by keeping busy. They put away the camera, lights, and film stock on which the day’s activity has been recorded.

It’s the calm after the porn, and any hint of normalcy in the bedroom was forced.

Outside the room, the rest of world got on with its own business. The rest of the world that is, except for right outside the hotel room door. Unbeknownst to anyone in the room, stood two muscular men. Greased jet-black dyed hair, wearing large rings, and blood-red satin sports jackets. They stood in anonymous silence. Hearing that the carnal activity inside the room had stopped, they nodded, and smiled. They pulled back, and disappeared down the corridor.

It’s a quiet summer afternoon in New York City, and everyone seems to have got what they came for.

*

Phil Russo. New York City. Seven years earlier, in 1970.

After kissing his wife and two sleeping daughters each morning before dawn, Phil Russo took the subway from Brooklyn to Manhattan to get to the police precinct where he checked in each day. No matter the season, it was always dark when he boarded the poorly-lit train. It was a jarring way for a transit cop to start his daily shift, but it was appropriate: everything around him was a reminder of his chosen career.

If you traveled the New York subway system in the 1970s, you’d never erase it from your memory: the graffiti-strewn train cars were home to aggressive panhandlers, drug-addled hustlers, and threatening gang members who resembled central-casting hopefuls for the movie ‘The Warriors.’

And if you never traveled on it, count your blessings. It was the most dangerous transit system in the world, and you felt relieved each time if you got out without being manhandled, molested, or mugged.

New York crime rates skyrocketed in the 1970s, and the subway was a jacked-up magnet for lawlessness. Each month saw hundreds of assaults, rapes, and murders on the trains and in their interconnected, dark maintenance passageways. Everyone knew about the problem, most everyone was ashamed by it, but no one seemed able to do a damn thing about it.

At one point, visitors arriving at New York City’s airports received pamphlets welcoming them to “Fear City.” The skull-emblazoned documents advised them “not to take the subways under any circumstances.” Robbery was so pervasive on the Lexington Avenue line that it was nicknamed the “Mugger’s Express.”

As for Phil, he’d been plunged into patrolling the transit system frying pan as a fresh-faced rookie transit cop in 1970.

Phil was a proud and sturdy Italian-American, a no-nonsense believer in family, law enforcement, and the city of New York – not necessarily in that order. From the start, he was fiercely proud to wear the badge for his hometown. The New York Police Department (NYPD) was a different beast from other law enforcement agencies: tougher, more merciless, ruthless even. Unlike police departments in Chicago or Los Angeles that vowed to ‘serve’ or ‘protect’, the NYPD’s motto was unequivocal: ‘Fidelis ad mortem,’ it warned. Faithful unto death.

Today, Phil still shakes his head at the enormity of the civic problem faced by the force when he first started. He remembers: “The Transit Police force covered a huge footprint. The Times Square subway station alone was immense. And we weren’t working smart: take our patrol patterns, for example – they were the same every day and therefore completely predictable. That meant criminals knew exactly where we were gonna be at any time. They could set their watches by us, and avoid us each day by staying one step ahead. Or one step behind.”

As subway violence increased, new tactics were introduced. The rearmost train cars were shut down at night, and a ‘war on graffiti’ was declared. The result? Not much. Arrests went up marginally, sure, but violent crime rates remained unaffected.

“Nothing we did seemed to work,” Phil remembers. “And the system was losing commuters every week – which in turn meant less money to fix the aging infrastructure. Train malfunctions were common, carriages were filthy, windows were frequently smashed. There was never a light at the end of the metaphorical tunnel.”

And then there were the mole people.

They were called them ‘mole people’ because they rarely ventured above ground. The thousands of tunnels descended to a depth of 60 feet beneath street level. Hundreds of homeless people made it their home. It was a city beneath the city, and its inhabitants hid from anyone who tried to get them out of there.

During Phil’s trips down into the inky bowels of these mazy passages, he was sometimes assaulted – hit on the head with a broken-bottle, or struck across the back by a sharp-edged shovel. Once he only avoided being skewered by a pick-axe when a colleague pushed him out of the way at the last second. Each time, Phil picked himself up, brushed himself off, and went back to work.

And hard as he tried, Phil couldn’t shake the mole people from his head. They faced him down during the day, and they came back to him in the darkness of his dreams. He didn’t share his recurring night terrors with his wife or friends, and he definitely didn’t mention them to his colleagues. After all, Fidelis ad Mortem has gotta mean something, right?

After years on the beat, Phil wanted a new role in the NYPD. He made his feelings known to his superiors: he’d appreciate a change, a different challenge. Ok, said the senior brass. They liked him and they didn’t want to lose him. And so, a few months later, he was transferred onto the streets of midtown, a neighborhood that included the notorious area around Eighth Avenue and Times Square.

It was a change, alright. But Phil had climbed out of the frying pan and walked into the fire.

*

Michelle Lake. Queens NY. 1972.

Michelle Lake didn’t just dream of swimming with dolphins, she thought about them every waking day – unusual for a Jewish girl growing up in an immigrant Brooklyn neighborhood in the 1960s and 70s.

While Phil Russo was patrolling the subway, Michelle was daydreaming her way through high school classes, wishing she was working in a sky-blue aquarium.

Her parents had come to the country from Poland and, like many of their generation and background, they were political and left-wing. The source of Michelle’s father’s ideology was white-hot anger and resentment, pure and simple. And he had good reason to be furious. He’d been a happy-go-lucky kid, but after fighting in the Second World War in Europe, he’d returned from the conflict a different man. He’d been one of the soldiers responsible for cleaning out the gas chamber ovens. And what he saw there changed him forever. For years after, he suffered from PTSD, waking up screaming in the middle of the night unable to shake the images from his mind. Now he was a staunch communist living at the heart of a capitalist empire, and if you pushed his buttons he’d explode. Heated discussions dominated his household: he believed that the working man was being exploited, and that the inequities of the free market were inherently evil.

Michelle’s introduction to politics started early – she was taken to marches in Washington to protest the Vietnam War, and met radicals like Angela Davis. But she didn’t see much of her father – he slept during the day and drove a New York taxi at night, a job he hated. He was a distant figure to her.

As Michelle remembers: “I lived in a house with an angry, wounded man that loved me, but his psychological injuries affected us all. My parents did their best, but they were emotionally absent and I felt it.”

The intergenerational pendulum swing meant that Michelle grew up with different aspirations. She remembers: “Rather than become political like my parents, I was driven to become spiritual instead. I turned to art and music, and looked for deeper answers to life.”

Michelle obsessively listened to hippies like Carole King and Peter, Paul and Mary, and taught herself to play the guitar. She wrote poetry and dozens of songs. She even got the chance to star in a TV commercial for a local milk company when she was a child.

It was a turning point. Shooting the advert lit a spark in her: “I decided I wanted to act,” she remembers. “I asked my parents if I could go to stage school. My mom dismissed the idea. Perhaps it was a money thing, but it also wasn’t the sort of activity families in our neighborhood did. The idea got dropped, but it lingered inside my head.”

At school, Michelle did well and had friends, but as a teenager she became shy and insecure. And as she grew older, her troubled home-life and low self-esteem led to bulimia. When it got bad, she’d cut class and hide the absences from her parents. On one occasion, her mother caught Michelle purging in the bathroom. She dragged Michelle to a psychiatrist. The expert’s conclusion was that the act of sticking her finger down her throat was probably a sexual issue. Nothing to worry about, he said. She’ll grow out of it eventually. As her bulimia wasn’t diagnosed, it wasn’t treated. And so it got worse.

Michelle’s search for self-knowledge may have lacked self-awareness, but it was defiantly earnest. By the time she hit 18, she’d already tried all the eras self-discovery fads. EST, Mind Dynamics, Primal Scream Therapy. You name it, she’d chanted it, confessed it, or shouted it. They didn’t all work, but that didn’t stop her searching.

Her best friends came from that scene too, including Erica, a girl of her age who became her best friend. Eventually she felt confident and empowered enough to move out of her parent’s home, and start a life on her own.

*

Phil. Times Square. 1973.

The first thing that hit Phil in his new job was the smell.

It was obvious from the first day he started patrolling the midtown streets: “The whole Times Square area had its own unique odor,” Phil recalls. “It was a damp, foul funk that came from the discarded garbage. The trash would lay in the sun for days. Nobody seemed interested in cleaning it up, so the stench lingered, and I smelled it everywhere. After a while, I equated that smell with the sale of sex.”

Phil’s new beat was a world away from the subterranean realm of the subway. As he walked the dirty, unforgiving streets, his life was now populated with a different kind of nemesis: peep shows and adult movie theaters.

Every day, Phil strolled past the grand old theaters from a bygone era, now grinding out pornographic films round the clock. He kept a close eye on the peep show machine operators that collected heaps of quarters in exchange for exhibiting the most explicit sex you could see in the city. And he was on a first-name basis with the bookstore owners, theater managers, hookers, and pimps that were denizens of the Deuce. Criminal activity was so brazen that commuters often had to step around prostitutes soliciting johns and climb over junkies just to get to work. He saw beatings, stabbings, shootings, prostitution, and drug deals – all conducted out in the open.

But it was the tourists that Phil found most amusing. He says: “I’d see these green out-of-towners walking down the street paralyzed with fear. They’d be huddled together, clutching their bags, afraid they were gonna get robbed.

“I’d look at them and say, “What the heck are you doing here?”

“They’d mumble, “We came to see Times Square.”

“I’d reply, “Well, you’ve seen it. Now get outta here before you see some real trouble!”

Phil worked hard. He had to. The police department lacked sufficient manpower, so officers like him were on call around the clock. And if he wasn’t walking his beat, Phil was back at the precinct or in the courts, processing the arrests he’d made.

It was a never-ending cycle of arrest-to-paperwork-to-court. Before long, the hours created a problem for Phil with his old lady. She’d been pleased when he’d got out of the trauma of the transit patrol, but now he was coming home even less, complaining about his workload, and often sleeping at the precinct. It seemed like she and the kids rarely saw him anymore. And when he did sleep in his own bed, his cold-sweat nightmares often woke her up.

Phil was getting it from all sides: “It was a brutal time to be a cop,” he says. “When we busted bookstores and theaters, a crowd would form outside, and they’d boo and jeer us as we loaded offenders into the paddy wagons. That shows you the level of support we got from the people we served.

“One day, a front-page article in the Daily News pictured two cops breaking into their own police car. Each of them thought the other had the keys, so they got locked out. Some journalist figured that was a funny headline for the city. We were being turned into a laughing stock.”

Sometimes Phil suffered even more than just being the butt of jokes. Because of the city’s budget woes, he usually patrolled the streets alone. If he got into trouble, his only recourse was to radio for help and hope that backup arrived before it was too late. As he describes it, “I got into scrapes, I picked up injuries, and I still have the scars. There was little respect for the uniform.”

But when Phil sat down at the bar at the end of a day, his biggest complaint wasn’t the long hours, or the budget cuts. It wasn’t the lack of respect, humiliation, or threat of physical violence either. It wasn’t even not seeing his family as often as he wanted, or his wife bitching that he was an absent father.

The biggest problem for Phil was that he didn’t think he was doing anything useful.

Policing Times Square wasn’t just an uphill battle – it was a losing one: when the cops arrested a hooker, she’d be back on the same corner the following day. When they shut down a bookstore selling 8mm sex loops, the owner would pay the fine and re-open immediately. And when they busted and closed a theater exhibiting an obscene adult film, the managers would just appeal to the courts and re-open the next morning. The sex business in New York was a Hydra, regenerating its lost heads instantly, and policing it was a Sisyphean task.

And even if Phil was successful, even if he did manage to secure the conviction of a porn theater manager or a bookstore assistant, these lowly people were just pawns of the sex business – and Phil wasn’t interested in busting the balls of the little guys. As he describes it: “We arrested these schmucks all the time, and ended up with thousands of reels of film, some petty cash, a few sad-ass clerks, and nothing more. I felt sorry for them. They were mostly Latino, and the owners took away their green cards to make sure they returned to work each day. It wasn’t their fault they worked in these places. What I was doing was just tackling the symptoms of the problem. We needed to do something different. We needed to attack the root cause.”

Phil was right. Everyone knew the mob controlled the theaters, massage parlors, bathhouses, prostitution rings, and gambling dens, and that they were prime suppliers of sex films and magazines. But the mafia dons managed their business interests from afar, and the police were rarely able to touch them.

Phil wanted to make a difference. He wanted the chance to take on the real offenders. The guys who were making the big money. He just didn’t know how.

*

Michelle. Queens. 1975

After graduating from high school and leaving home, Michelle went to City College in New York.

She was a serious and dedicated student, but bulimia still cast a heavy shadow over her life. She says: “My roommates caught me throwing up a few times. They dragged me out of the bathroom to help, but they didn’t know what to do. They meant well, and tried to make me feel good about myself, but the problem wasn’t just that I thought I was fat – it was about deeper issues and insecurities.

“It was about the family environment I was raised in. It was about my parents, and how they had difficulty expressing their love for me. It was about how I never felt accepted.”

After a year in college, Michelle wasn’t happy – so she quit, with one destination in mind. She’d scraped together enough money for a one-way bus ticket to Miami. She remembers: “I was determined; I just wanted to work with dolphins. I’d fallen in love with the idea at 15 when I wrote a biology report on animal communications. When I graduated high school, I wrote letters to marine biologists all over the country begging for a job – but heard nothing back.”

Michelle wasn’t necessarily interested in being a biologist or a veterinarian – she just wanted to just be around dolphins. She hoped that if she showed up in person, she could get some kind of marine work in Miami. For a brief moment, her hopes were raised when she met a guy who worked at a local aquarium. He offered to sneak her in after-hours so she could swim with newly captive dolphins. It was her dream come true.

That night, Michelle slid into the water and into a new state of mind. She knew dolphins were unable to make facial expressions, but their eyes told a different story. She felt their curiosity and interest as they circled her in the pool. She floated weightless as they gazed at her in the semi-darkness.

But it proved to be a one-off moment of hope. The aquarium worker disappeared. Michelle found a job waitressing but struggled to make ends meet. When she conducted an audit of her worldly wealth by slipping her hand into her pocket, she realized it was time to return to New York.

Michelle was back where she’d started.

*

Varla Romano. 1975. Midtown New York.

As divisions of the NYPD go, Public Morals was known as an abrasive place to work. On top of that, equal treatment for female police officers in New York was still in a theoretical phase.

So when Varla Romano transferred to the Public Morals Squad for Manhattan South – a force that covered the southern tip of the island right up to 59th Street and encompassed the entire Times Square area – she braced herself for impact.

A second-generation Italian-American, Varla was an intense, pugnacious, and determined character. She had to be to break with generations of cultural tradition that frowned on women taking jobs meant for men. She’d already achieved the impossible by making her family proud of her career in law enforcement, even if they found it difficult to accept at times. “Numu fai shcumbari” was the frequent admonition from her brothers and uncles: “Don’t embarrass us.”

Varla developed the experience and credentials to back up her determined self-belief. She carried a playground sense of justice to work, not to mention a substantial chip on her shoulder. But if Varla thought she was prepared for the job, she was still surprised by what she found when she turned up at 137 Center Street for her first day’s work.

The office was a wide-open room full of egocentric mavericks – a gaggle of wise-cracking, street-wise, plain-clothes and plain-speaking alpha-male cops. And there were three types of new recruits these guys didn’t like: those who knew nothing, those who knew everything, and women. As hard as she looked, Varla couldn’t see another woman working there.

Public Morals had been set up years earlier to enforce all laws related to vice: principally the moral trifecta of prostitution, liquor and narcotics violations, and illegal gambling in the city. Or, sex, drugs and rotten ho’s, as cops referred to it.

In recent years, a fourth component had been added: obscenity. This newly critical concept included the proliferation of all things considered pornographic, such as bookstores and adult films.

So perhaps it was no coincidence that very few women turned up at Public Morals: they just didn’t fit into that a scene that traded in sin, right? Plus there was the belief was that a woman cop would just attract unwanted attention in a criminal world inhabited by male sleazebags.

The difference between uniformed cops on the streets and plainclothes members of the Public Morals squad was like night and day. Street cops arrested petty criminals doing dumb stuff. You know the deal: ‘Suspicious looking activity.’ ‘Loitering with intent.’ ‘Disorderly conduct.’

The Public Morals squad was different. They went undercover – behind the scenes, into massage parlors, strip clubs, and gambling dens. They looked for the real instigators, the suffering victims, and the powerful ringleaders.

It was a complex world, both legally and morally. For example, how do you make a bust for prostitution in one of the Deuce’s flourishing massage parlors? The quickest way was to get a working girl to offer you sex for money. But what if the girl asked you to strip before she’d discuss any details? The hookers were smart enough to know that separated out the johns from the cops, because Police Department regulations forbade officers from taking off their clothes to gather evidence.

The bottom line was it was hard for Varla to break into this male-dominated world. It got farcical at times. One of her first jobs in Public Morals was part of a push to get rid of prostitution in midtown. The authorities decided to use a dormant law requiring all arrested hookers to be examined for VD, which would allow the city to temporarily keep the prostitutes in custody pending test results. The guys at the top felt that keeping the girls off the streets even for a few days would have an impact on the problem. Trouble was that none of the guys in Public Morals wanted to touch this idea. So they nominated Varla to make sure the girls got their cooches swabbed before being thrown into a cell.

Were Varla’s colleagues grateful that she did this? Were they hell. They just laughed, and gave her a new nickname: ‘VD Varla.’ The name stuck, and Varla had another battle to fight.

After a while, her pugnacious attitude started to win some of them over. Varla started to be included in the raids. She remembered the first time. It was when they busted a burlesque house on 42nd Street. The cops went in and grabbed the manager and two performers – and charged them with public lewdness, obscenity, simulated sex acts, and sodomy.

Varla still laughs about it: “To this day, I don’t know how we managed to make a bust for simulated sex acts AND sodomy. I think most of the guys I worked with thought sodomy was a blow job. I gave up trying to explain it to them because they just said I was a pervert.”

The work was often thankless: like when they raided the Zoo, a mafia-owned late-night discotheque where teenage kids were being offered amphetamines with their orange juice. Varla herded up the horny, paranoid, red-faced kids, and took them back to the station for some pointless interviews – that were entertainingly surreal.

Or another time, when they turned up to bust a massage parlor for not having a license, and found that overnight the location had turned into a ‘Rap Club’ – a place where you could pay for a conversation. Nothing wrong with that, right? For a modest fee, ‘beautiful conversationalists’ were now available to have private deliberations on any subject with you in clandestine cubicles. Nothing more. It was the same sex business, sure, but they couldn’t be busted for offering chat. One brothel even changed its identity within a single afternoon, becoming a body-painting establishment. The new businesses were all legal and above board. Move on – nothing to see here. There was nothing the cops could do. And as soon as they moved on, the businesses went back to sex.

But sometimes, Varla did something she felt good about. Like busting into a hotel room where a teenage girl had been kept against her will. The underage waif had arrived at the Port Authority the previous week, and had been offered enough candy-kindness by a macaroni pimp on the Minnesota Strip to get her head turned. He’d lured her into a seedy hotel where he forced her to have sex with a dozen men a day for money. Varla received a tip-off from a friendly hotel clerk, and so she broke into the room to rescue the girl. It may have been just a rare moment of success, but she’d take it.

Varla worked hard, fought her corner, had minor successes, and gradually started to be accepted. The most she could hope for was to be was one of the boys.

*

Phil. Times Square. 1975.

After a few years of experience earned on the pornography-infested midtown streets, Phil Russo transferred into the Public Morals Squad. He was a valuable addition. After his time underground patrolling the subway as a transit cop, and then his time on the streets of midtown, he was finally where he wanted to be.

He’d come into Public Morals with a mission of his own. He was less interested in busting illegal poker games, gender-bending queer bars, or happy-ending rub-and-tug emporiums: Phil wanted to break open the rapidly expanding XXX film business. He’d seen the never-ending stream of new pornographic movie titles that premiered each week in the midtown grindhouses. He knew that any racket that operated in these gray areas of legality, and that was making outlandish profits, had to be fertile turf for the mob, so he’d decided he’d make the porno trade his target.

Phil learned the ropes fast: He learned there were two magic phrases that you’d hear from the top all the time.

First: A ‘new police crackdown’ was always being announced – part of ‘ongoing efforts to clean up midtown Manhattan.’

Second: As part of said crackdown, the police would be ‘investigating links with organized crime.’

Phil knew the first was bullshit. Every week brought a ‘new crackdown.’ There was always talk that the city was going to clean up Times Square for good. Whenever a new congressman or senator came to power, promises were made that everything was going to change. But it never happened. When Abe Beame was elected mayor in 1974, he pledged a significant midtown cleanup. In fact, Beame promised to promote legitimate business activity in Times Square and the neighboring areas, but as soon as the election was over, no new funds were allocated. In fact, funds were cut. And Beame turned his attention elsewhere.

Which made the second magic phrase all the more important – and more futile: if the crackdowns were worthless, then how could Public Morals establish indictable links with organized crime? Phil called the problem ‘cracking the code’. Shorthand for establishing the identity of who ultimately owned the most lucrative parts of the sex businesses, such as the distribution centers for pornographic materials. Expose who was raking in the profits.

And there was a boatload of profits, because New Yorkers were clearly eager to buy what was on offer. According to police estimates in 1976, the larger Times Square book and peep stores, like Show World and Jolar, were easily grossing tens of thousands a day. Someone was getting very rich, but the NYPD didn’t have the tools to identify them, let alone go after them.

Sure, fines were levied when convictions were obtained, but they were a drop in the bucket compared to the cash being made. In fact, the mob were rumored to welcome the busts because they were splashed across the newspapers – which meant free publicity for their businesses. Hell, the fines were cheaper than ads in the Daily News.

Inside the Public Morals offices, diagrams of organized crime networks were plastered on the walls. Phil remembers, “The mob was smart in hiding their involvement. They rarely sold sex films and magazines directly to stores in New York. Instead, they had their product shipped outside of the city to smaller wholesalers, who then ran the goods to the porno shops in Times Square.”

The problem for Phil was that insider information was poor. Undercover officers weren’t coming back with anything useful. And to make matters worse, many of the cops were crooked. For a modest fee, they would let porno theater managers know the police were on their way before they could bust them.

Public Morals was so desperate for hard information they even started to read local sex magazines to try and find out where the action was taking place. On one occasion, they gleaned useful information about an illegal massage parlor from an article in Cheri magazine. A successful raid followed. Which was good. But it was pretty embarrassing when your best informant was a jizz mag.

*

Michelle Lake. Times Square. November, 1976.

After Michelle’s money and luck ran out in Miami, where she’d gone to try and find work with dolphins, she returned to New York, She worked in a series of waitressing jobs, and sweated long hours behind bars to pay her bills as she tried to figure out what to do next.

She was now 22, a college dropout, damaged family relationships, and had a failing romantic life too. Michelle’s latest boyfriend was only the third guy she’d slept with. She explains: “Emotionally, I was repressed and shut down. I was still bulimic, and couldn’t understand why anyone would want to look at me. Whenever I was physically intimate with someone, I was guarded and I would hold back.”

But Michelle was always a searcher, and a door in her mind had been left ajar by group therapy. She knew she wanted to be more liberated – she just didn’t know how she was going to do it.

One night, a regular came in for a drink. Sue was an exotic dancer at a club down the street called the Melody Burlesk. She’d often stop by the bar at the end of her shift, carrying her damp stage costumes and a purse full of singles carefully smoothed of the wrinkles inflicted by sweaty eager hands. Michelle was intrigued. She drilled Sue on what it was like to dance naked in front of men. Finally, to free herself from the interrogation, Sue suggested that Michelle stop by the Melody and see for herself. The mere thought was intimidating to Michelle, so she enlisted her friend Erica for courage, and together they headed to the Melody the following night to catch Sue in action.

The format at the Melody was simple – each dancer did a 20-minute set several times a day, and the audience would leave tips on the tiny stage for the performers. Michelle and Erica took seats and watched, amazed by what they observed. Sue seemed like a goddess under the spotlight: strong, beautiful, and in total control. The dollars quickly piled up, crumpled balls of appreciation. More than anything, the men in the audience left their mark on Michelle. She remembers: “They seemed like vulnerable, lonely children looking up at Sue. It was poignant. It stayed with me for ages after.”

After her dancing shift, Sue introduced Michelle and Erica to the Melody’s manager. It was only years later that Michelle learned the Melody was started by a mild-mannered Jewish accountant named Albert R. Kronish with support from investors. It had been intended to be a last bastion of old school burlesque dancing, but it had quickly succumbed to the linked forces of libido and commercialism. The Melody introduced the concept of the ‘Mardi Gras’, allowing dancers to sit naked on customers’ laps for a $1 tip. This was followed by the ‘Box Lunch’, where a patron’s dollar could buy him a few seconds performing oral sex on his favorite dancer.

But that night, the manager could see that Erica and Michelle were intrigued so he offered them try-outs. Erica jumped at the opportunity to give it a go and urged Michelle to do the same. Michelle was apprehensive, but accepted with trepidation. With guidance from Sue on how to move, what to wear, and how to remove it, the night of their trial audition arrived. Rather than being nervous, Michelle found herself strangely excited, remembering the looks of adoration from enthralled customers.

She stepped onto the stage. From the start, the shy, body-conscious Michelle started to shine. Whatever inhibitions she had were shed with each article of clothing, melted by the appreciative gaze of the audience. Men’s attention, which had once seemed unlikely and mildly threatening, ignited Michelle’s confidence, and did more than all of the self-help workshops she had attended. She was hooked, and agreed to do it again.

Soon, dancing on stage took the place of tending behind the bar. Both Michelle and Erica became Melody regulars, pleased with the work and relieved of the financial stress they’d regularly borne. After a couple of months of solo routines, Michelle and Erica convinced the manager to let them combine their sets and act out a scene together. Their sexy versions of Little Red Riding Hood and other fairy tales soon became hits with the afternoon raincoat crowd.

Michelle basked in her new success – with little thought for the sleazy Times Square environment it contributed to.

Michelle Lake

*

Michael Codd. November 1976.

Michael Codd was the new big cheese, the most important man in the New York Police Department, and he looked every inch the Chief Commissioner.

Six feet tall and 200 pounds with silver hair, steel-blue eyes, and a granite jaw, Codd commanded near total respect of the 30,000 strong police force. He was an old-school, old-fashioned policeman’s policeman, known throughout the city’s station houses as ‘Chief Straight Arrow.’

No one had better credentials to take over the position: he’d joined the state police back in 1939, and had risen seamlessly through the ranks to become Commissioner. And when Codd was appointed top dog, the reaction was unanimously positive from all levels of the force.

Codd viewed the police force as a large extended family. He made a point of frequently visiting different precincts to speak with the men and women of the department. He was always greeted as a hometown hero, met by warm applause, alpha male handshakes, and requests for photos.

New York Police Commissioner Michael Codd

But however positive the reaction, it couldn’t mask one significant stumbling block: it was the worst possible time for anyone to be appointed Police Commissioner. If success in life is a matter of luck and timing, Codd was flat out of both.

By the time Codd took the helm, New York City’s financial crisis had gone from bad to critical, and the fall-out was severe. The city’s economy had been rocked by the decline of manufacturing and flight of the white middle class to the suburbs, resulting in falling tax receipts that risked the city defaulting on massive loans. City officials scrambled to patch together one plan after another, each cutting back on social and municipal services to save the city from declaring bankruptcy. No matter the plan, the Police Department was always a prime target for cuts.

From 1976 to 1980, there was a hiring freeze on all city departments, including the NYPD. Worse still for Cobb was the forced lay-off of 6,000 officers, not to mention a complete freeze on all salaries and promotions.

The warmth that initially greeted Commissioner Codd’s appointment quickly turned to antagonism. Cops complained that Codd should have publicly resisted the cutbacks. The rot set in. Thousands of officers began street demonstrations during off-duty hours and there were talks of strikes.

When the normally understated leader described the reduction of manpower as “without parallel in the history of the department,” it was clear that his impeccably calm, gentlemanly demeanor was being sorely tested.

And of all the police departments to suffer, Public Morals was one of the hardest hit. Several hundred officers lost their jobs, decimating the ranks of the vice squad.

But on paper, the clean-up of Times Square remained a priority. So the big question was how to pick up the pieces of this financial devastation, and find more creative ways to crack the code?

*

Phil & Varla, Times Square. February 1977.

Phil and Varla were among the survivors at Public Morals. They were good at what they did, and maybe they were just lucky too. They kept their jobs, and lived to fight another day.

Against the unpleasant backdrop of job cuts and daily work challenges, the two of them forged a solid working relationship. Phil’s marriage was on the rocks, and he appreciated someone with an unsentimental attitude. If he ever wallowed, Varla just hit him round the head.

After working long hours, they often sat around with fellow officers, spit-balling ideas about how they could make any progress with so few resources. It always came back to the same question: how were they supposed to tackle pornography in the center of one of America’s biggest cities if old-fashioned police methods weren’t working?

One night at their regular bar down the street from the precinct, an officer shared a tidbit that caught Phil’s attention. The cop said that a few years back when the force was starting to turn its attention to obscenity, there had been a small but novel operation, which was kept largely under wraps. An officer had pitched the idea that the cops buy one of the existing adult bookstores in Times Square and install undercover detectives to run the place. The thinking was they’d use that access to identify porn’s real power brokers – the guys pulling the strings, flooding the Deuce with filth, and raking in ill-gotten gains. Miraculously, management had given them the green light.

Phil pulled Varla in and pushed for details – who’d ran that operation, what did they learn, what happened to the sting? But their fellow cop was short on specifics – he said the effort was shut down not long after it started, supposedly due to a lack of results, but nobody knew for sure because it was kept on the down-low.

The idea struck Varla as ridiculous, but she saw something in Phil’s eyes she’d come to know in their time together. It was a look that combined curiosity, scheming, and determination – and once it infected Phil, it was almost impossible to cure him of it. “He was stubborn like that,” says Varla.

Back at the precinct, Phil did some digging. Most everyone was tight-lipped about the former operation but he was able to eke out a few details. The budget had been a paltry $2,000, which came from a group called the Citizens Committee on the Control of Crime in New York. The force took over an adult bookstore at Eighth Avenue and 50th Street, and it got as far as installing hidden tape recorders and cameras. They were told to only sell soft‐core books and magazines – an approach that would keep them on the right side of the law even though it lost them a lot of customers and limited their success at breaking into the mob. And then the operation had been terminated abruptly. And no one spoke of it again.

As the weeks went by, Phil couldn’t let the idea drop. He was sure it was just the type of innovative thinking they needed to adopt. Phil felt he knew exactly what Public Morals needed to do. Ever since the high-profile success of ‘Deep Throat’ in 1972 and the slew of X-rated films that followed, it was clear the big money was in the distribution of porno movies. If the vice squad could break into that world, they’d have a better chance of getting at the money men pulling the strings.

Phil’s idea was simple: he would lead a team who would form a fake porn production company and they would pretend they had films to sell. They’d get to know who else was creating the movies and, more importantly, they’d get in with the connected crowd who was funding and selling them.

When Phil shared his scheme with Varla, she thought he was joking. But then she saw the signature look in his eyes and realized he was dead serious. “I nearly fell off my chair,” she says today. “I mean, the NYPD making porn movies? Really?! Phil said we wouldn’t actually shoot ‘em, we’d just do everything short of filming so we could make the connections. It seemed like a crazy idea to me, but he was determined.”

Varla suggested they get feedback from the rest of the squad. And like Varla did, at first they laughed. Then they got curious. Varla figured taking the idea to the boss would put an end to it. She just hoped they wouldn’t come out department laughing stocks in the process.

*

Three different characters trying to find their way in 1970s New York: Phil Russo, the idealistic cop desperate to defeat the sex netherworld of Times Square. Michelle Lake, the hippy, bulimic teenager who just wanted to work with dolphins and ended up finding her true self by stripping in front of adoring men. And Varla Romano, the combative detective trying to fight the sex businesses in the city, while fighting for her own recognition in the Public Morals Squad.

Their paths would cross briefly in a hotel room at JFK airport in the summer of 1977, and their lives would be changed forever.

*

Tune in next week for Part 2 of ‘Cop Porn: When the NYPD Made an Adult Film.’

*

The post Cop Porn: When the NYPD made a Porn Film – Part 1 appeared first on The Rialto Report.

More Episodes

2015-08-30

2015-08-30

6

6

2015-04-19

2015-04-19

2014-12-14

2014-12-14

2014-11-23

2014-11-23

2014-11-02

2014-11-02

2014-06-29

2014-06-29

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2024 Podbean.com