103. How Computers Transformed Museums and Created A New Type of Professional

2023-11-13

2023-11-13

Museum computing work keeps the museum running, but it’s largely invisible. That is, unless something goes wrong. For Dr. Paul Marty, Professor in the School of Information at Florida State University, shining a light on the behind-the-scenes activities of museum technology workers was one of the main reasons he and his colleague Kathy Jones, Program Director of the Museum Studies Program at the Harvard Extension School started the Oral Histories of Museum Computing project.

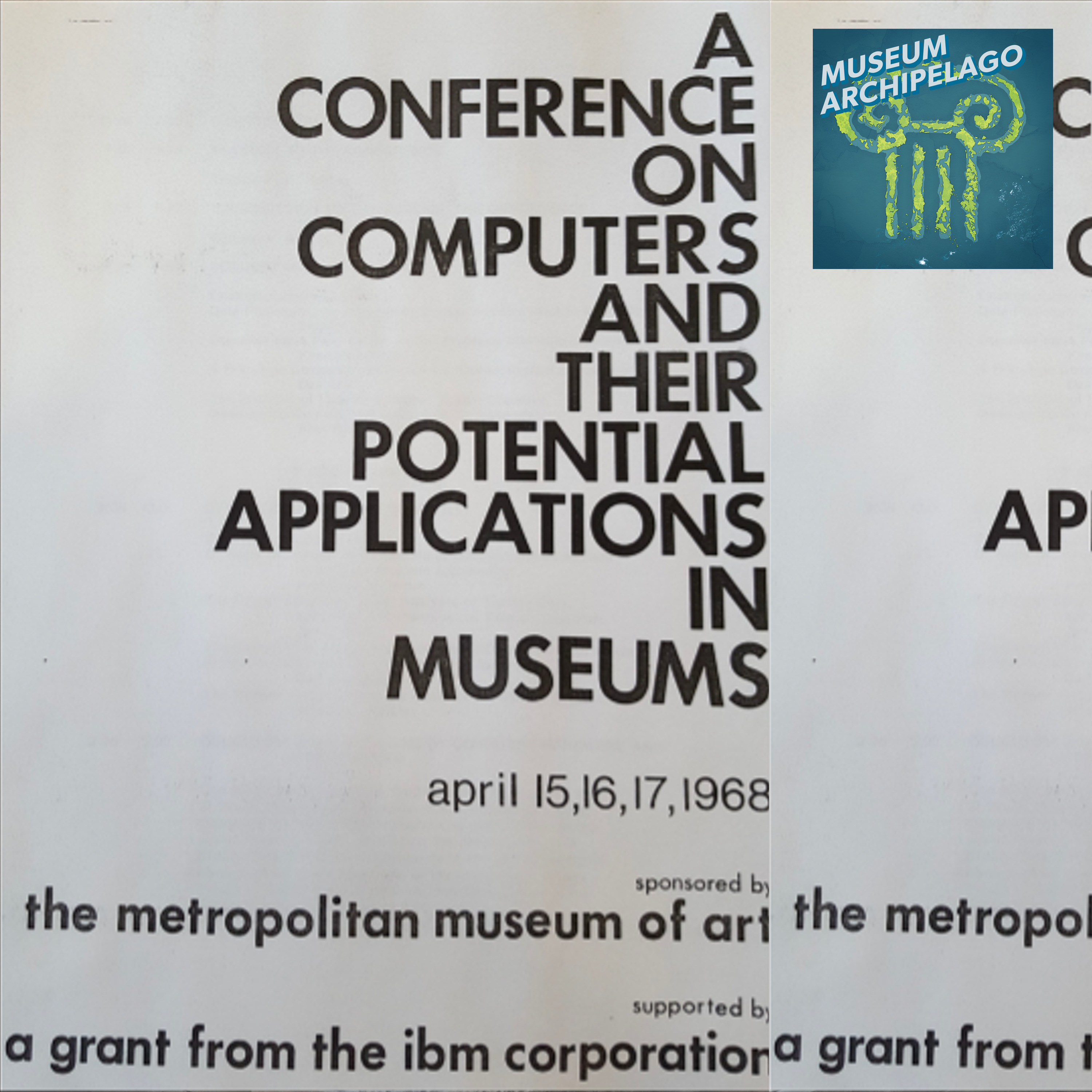

The first museum technology conference was hosted in 1968 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This prescient event, titled “Conference on Computers and their Potential Application in Museums” was mostly focused on the cutting edge: better inventory management systems using computers instead of paper methods. However, it also foresaw the transformative impact of computers on museums—from digital artifacts to creating interactive exhibits to expanding audience reach beyond physical boundaries. Most of all, speakers understood that museum technologists would need to “join forces” with each other to learn and experiment better ways to use computers in museum settings.

The Oral Histories of Museum Computing project collects the stories of what happened since that first museum technology conference, identifying the key historical themes, trends, and people behind the machines behind the museums. In this episode, Paul Marty and Kathy Jones describe their experience as museum technology professionals, the importance of conferences like the Museum Computer Network, and the benefits of compiling and sharing these oral histories.

Topics and Notes- 00:00 Intro

- 00:15 A Conference on Computers and their Potential Application in Museums

- 00:43 Thomas P. F. Hoving Closing Statements

- 01:41 Paul Marty, Professor in the School of Information at Florida State University

- 02:11 Kathy Jones, Program Director of the Museum Studies Program at the Harvard Extension School

- 02:18 Museum Computing from There to Here

- 04:08 The First Steps of Museum Computing

- 04:52 Early Challenges in Museum Databases Like GRIPHOS

- 07:00 Changing Field, Changing Profession

- 08:48 The Oral Histories of Museum Computing Project

- 11:32 Reflecting on the Journey of Museum Technology

- 14:12 Outro | Join Club Archipelago 🏖

Museum Archipelago is a tiny show guiding you through the rocky landscape of museums. Subscribe to the podcast via Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Overcast, Spotify, or even email to never miss an episode.

Join the Club for just $2/month.

- Access to a private podcast that guides you further behind the scenes of museums. Hear interviews, observations, and reviews that don’t make it into the main show;

- Archipelago at the Movies 🎟️, a bonus bad-movie podcast exclusively featuring movies that take place at museums;

- Logo stickers, pins and other extras, mailed straight to your door;

- A warm feeling knowing you’re supporting the podcast.

Below is a transcript of Museum Archipelago episode 103. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, refer to the links above.

On April 17th, 1968, less than two weeks after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, the first computer museum conference was coming to a close at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

This conference was hosted by the recently-formed Museum Computer Network, and had a hopeful, descriptive title: A Conference on Computers and their Potential Application in Museums.

At the closing dinner, Metropolitan Museum of Art Director Thomas P. F. Hoving acknowledged that “for some these three days have an unsettling effect” and that “these machines are going to put us on our toes as never before” but summarized, “the whole idea of a computer network is generating momentum, and is forcing upon museums the necessity of joining forces, pooling talents, individual resources, and strengths.”

Paul Marty: When I tell students that there is a group that has been meeting annually since 1968, To discuss problems related to the use of computers and museums, they find that hard to believe. That seems like a long time ago, and I guess it is a long time ago. But museums were always on the cutting edge of trying to figure out how to use this technology. Maybe not everybody was on board, but there was always somebody who was pushing that story forward.

This is Paul Marty, whose work focuses on the interactions that take place between people, information, and technology in museums.

Paul Marty: Hello, I'm Paul Marty, Professor in the School of Information at Florida State University.

Professor Marty, along with his colleague Kathy Jones, are collecting stories of the people behind the computers behind the museums as part of their Oral Histories of Museum Computing project. A selection of stories from the project will be published as a book.

Kathy Jones: Hello, my name is Kathy Jones, and I'm the. Program Director of the Museum Studies Program at the Harvard Extension School.

The key question that both Jones and Marty want to answer is how did we go from there to here?

Paul Marty: How did we go from a world where curators were saying there will never be a computer screen in our galleries, to a world where when you're setting up a new exhibit the first thing you ask is where should we put the iPads? How do we go from a world where we will never share digital images of our collection on the internet to a world where there are hundreds of millions of open access images in the public domain on the internet by museums?

To answer that question, Jones and Marty looked to their own experiences going to the many museum computer conferences that came after. But they both underscore how remarkably prescient that first meeting proved to be.

Kathy Jones: That first Museum Computer Network meeting I just want to emphasize the importance of meetings, even that early and now of bringing new ideas to the field. everything evolved based on the technologies that we had at hand. And museums weren't the first to adopt something like a scanner or to do multimedia, but as soon as we saw the possibilities, we certainly began to do that.

Paul Marty: I actually just pulled up the table of contents for the conference proceedings for the very first Museum Computer Network Conference. And, there were a lot of papers in there sort of predicting what the future of computers in museums were going to be. And of course most of them were focused on inventory control and this. But there were also people talking about computer graphics and what that was like at the time. J. C. R. Licklider who is the the founder of ARPANET, which is , the original backbone of the internet, was there and spoke about the current state of computer graphics technology in the late 1960s, and , he was predicting a world where there would be digital images of museum artifacts, where people could have an interactive art museum where you would use digital computer images of artifacts. And it took a while for us to get there, but it's wonderful that people were thinking that far ahead in the 1960s.

Computers first entered museums as a form of inventory management. Edward F. Fry summarizes in his 1970 review of that first conference, “the rapid increase in the size of museum collections in the United States has in fact reached such a point in many instances that a more efficient means of cataloging than that of the standard index card file has become a desperate necessity.”

Paul Marty: Remember the final scene at the end of Indiana Jones and Raiders of the Lost Ark, right? So many of the Smithsonian warehouses look exactly like that and it's really easy to see how things could get lost there for a very long period of time. You have more stuff than you have staff and time to deal with.

The early inventory management systems were limited to only a few variables and lots of manual work, as Kathy Jones learned when she started her career at the Florida Department of State.

Kathy Jones: I worked on a mainframe computer to be what they called the keeper of the Florida master site file. That was a large database, or is, that keeps track of all of the archaeological sites and historical properties in the state of Florida.

Kathy Jones: It was a database called GRIPHOS, and it was used by archaeological groups, the State Historic Preservation Office. There was nothing visual about it, not even images or things like that. It was hardly relational, and every field was just about 80 characters. I mean, this is so long ago, Ian, that we had to use punch cards to do the data entry and then have them read per computer in batch form. Pretty archaic.

GRIPHOS stood for General Retrieval and Information Processor for Humanities Oriented Studies – I can’t get enough of the direct naming conventions of this early computer history – and it was actually published by the Museum Computer Network, the organization that hosted that first conference in 1968.

Paul Marty: So GRIPHOS was the database system that ran on mainframe computers developed in the 1960s and disseminated by the Museum Computer Network. And part of the goal of the Museum Computer Network was to help museums learn how to use GRIPHOS to organize information about their collections. Kathy, I don’t know if you wanna talk about what it was like at the conferences…

Kathy Jones: It was the first attempt at standardizing information, and that was because we had limited fields and limited values, but it did lead to a profession-wide attempt to standardize how we describe all types of information. So not just the art world, but also the history world or the object world.

The early systems for cataloging collections were rather rigid, which meant that the museum staff had to get inventive to bridge the shortcomings. This process would repeat itself.

Kathy Jones: As the field changed we were looking at what the public needs were, we began to discuss early on where we would fit in the museum. What was our role now? Initially, it was a behind the scenes type of thing with registrars, museum registrars mainly, having to learn a new skill set. Having to be somewhat digitally based, and doing their job now with new technology. Then in the mid-1990s and later we could add imaging to that set. And we had to learn about scanners and what they might do to the art, or how we could use them safely and efficiently to process the image, because we're a visual field. And then we got into multimedia, and both, , in the gallery and online, and another skill set emerged.

Paul Marty: You went from physically plugging in computers and wires to figuring out how to present information in a way that can be used by people inside the museum, that suddenly people realize, “hey, there's people outside the museum with all this information as well.” And then this can also become used in exhibits in the galleries and then eventually online.

Paul Marty: It's just been a constant process of the museum technology professional having to keep up with those changing technologies, keep up with the increasing demands that keep getting put on them. They have to figure out how to use new technology to accomplish new goals. I think that this entire profession has evolved over the years to tackle these problems. Because when museums started doing this, there, there wasn't, you couldn't go to school for this.There wasn't a job title for this. Kathy talked about registrars. You were organizing the information on paper files behind the scenes and somebody said, “hey, look, we can do this better and faster if we start using a computer here.” And you're the one who had to figure out how to do it.

As museum technology professionals themselves, Marty and Jones realized that shining a light on this type of work would be a good basis for their next project.

Paul Marty: Kathy and I have worked together on a number of projects in the past. We published a book together back in 2008. We had been meeting to work together on another book for a long time and we had been meeting regularly once a week or so and chatting about different project ideas and I guess it was 2019 when we first started talking about an oral history project because among other things, we were inspired by the 50th anniversary of the Museum Computer Network, and they had done some work trying to capture some voices from the field and some of that history there, and we realized that there was a great need for that particular work.

Paul Marty: We were also very interested in the question of how do we shine a light on the behind the scenes activities of museum technology workers? Most of the people who do this job, you don't see their work. You see the end product of their work. You see the database, you see the website. You don't see what they're doing behind the scenes. Like most information technology workers writ large, not only is your work invisible in the sense that if you see me working, I'm probably doing something wrong, but the system that you built is also supposed to be invisible, right? It's supposed to be like plumbing. It’s difficult to work a job where if your work is visible, that means something has gone wrong. And so we were really trying to help both preserve the history and shine a light on that behind the scenes work that so many people don't see.

When I’m not doing Museum Archipelago, I work as a computer programmer making interactive exhibits in museums. That should put me neatly into the category of museum technology professional — but I have to admit that I made it to this part of the interview before realizing Marty and Jones include people like me.

Maybe it’s just a slight aversion to the term “museum technology professional” which has the clunkiness of those direct naming conventions of early computer history. Maybe it’s actually the perfect term.

Marty and Jones invited about 120 professionals to participate in their oral history project, successfully compiling 54 oral histories from individuals whose careers focused on bringing technology into museums.

Listening to the stories in this collection, which feature some past guests on Museum Archipelago, I’m struck that the types of problems museum technology professionals solve mirror my own experiences: computers in tight places on the gallery floor that nobody realized needed to be manually rebooted every few days, custom software running long after any who remembered what its for left the museum, and the wire that isn’t long enough to run from the exhibit floor to the server room.

Kathy Jones: “What we're doing also lends credibility to that invisible work and really does shine a light on it, bringing it out for the field, but also Paul and I both teach. So it brings it right to our students in a way that I think is important. I, in my museums and technology class, post podcasts for different topics so that my students can hear from Jane Alexander or other people in the field about what they're doing. And I mentioned Jane Alexander because she has been able to really raise the visibility of what she doesfrom the server room to the boardroom. And I think it's so important to see that we can have a voice, that we could be, if not part of th e C suite, that we're getting pretty close to being there so that other people understand what it means to be digital in the museum world now and not take it for granted.“

Paul Marty: We captured stories that people never heard before. These were the people who were making the magic happen behind the scenes. To get their perspective on that was just absolutely amazing. We didn't want to tell a chronological history of the field. That's been done. We are at center identifying the key historical themes and trends that cut across the past 60 years and really drove the field forward. And then telling that story, using examples. In the words of the very people who who did that work.

Which is remarkably similar to what Metropolitan Museum of Art Director Thomas P. F. Hoving predicted back in 1968 – that the only way to roll with the momentum that computers in museums generate is to get all the humans together, sharing resources and expertise. After all, no museum is an island.

Paul Marty: One of the things that I think surprised me as we went through and gathered these stories, analyzed these stories, was how positive and enthusiastic everybody was about the work that was done. Because you know, in a technology profession, it's easy to be negative. It's easy to say, well, we don't have enough resources. We don't have enough money. We don't have enough time. This is always the perennial problem. Of course, but when you step back and you take the 30,000 foot view and you look at what's been done over the past 60 years. And I think we heard this from every one of our participants. When you look at that, it's amazing how far we've come. And it's hard not to look at that scope and not come away with a positive perspective on what we've accomplished. And our hope with the book that we're writing is to convey that sense of enthusiasm to help inspire the next generation of people who are doing this technology work in museums

Kathy Jones: “Ian, thank you for giving us the opportunity to talk about something that we love.”

This has been Museum Archipelago.

More Episodes

2024-09-23

2024-09-23

2023-07-31

2023-07-31

2022-11-28

2022-11-28

2022-08-08

2022-08-08

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2024 Podbean.com