John Andrew Morrow on Gaza Genocide & "Islam and Slavery"

2024-01-27

2024-01-27

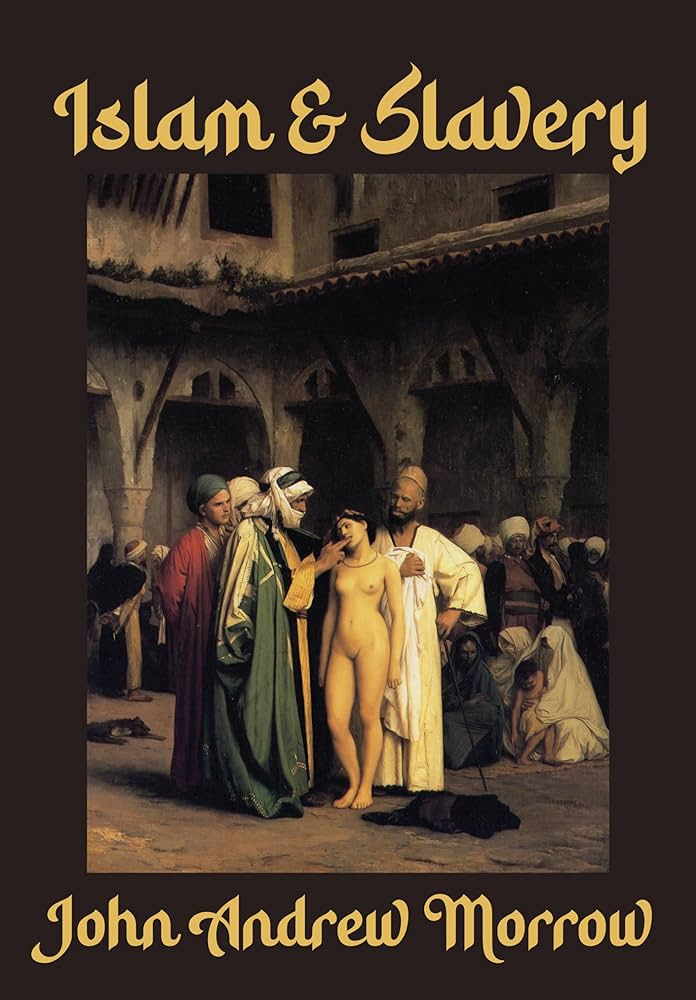

Islamic scholar John Andrew Morrow, founder of the Covenants Initiative, discusses his new book Islam and Slavery.

Everyone knows Islam is against debt slavery, the inevitable consequence of usury. But what about other forms of slavery? One school of thought holds that since domestic slavery was ubiquitous and unquestioned at the time of the Prophet (saas) and is not clearly and directly banned by Islamic scripture, it is permissible. In Islam and Slavery Dr. Morrow takes the opposite view: “The Qur’an encourages and even requires Muslims to emancipate enslaved people. As far as the exponents of Islam’s spiritual, moral, ethical, and egalitarian tradition are concerned, the Qur’an, the Prophet, and Islam introduced a system that would reform the practice of slavery and abolish it entirely and forever.”

Extract:

As an academic, I'm asked to peer-review articles that are submitted or to write reviews of books. Reading Religion, which is the name of the journal, sent me the list of books that were available for review and I proposed a few of them. They came back to me and asked me to review Slavery and Islam.

(Reads) In Slavery and Islam, Dr. Jonathan A.C. Brown, the Alwaleed bin Talal Chair of Islamic Civilization at Georgetown University, devotes over 400 pages to support his conviction that slavery and concubinage are permissible according to the Quran and the teachings and practice of the Prophet Muhammad. He is adamant that God and His Messenger allowed, condoned, and supported them. In his words, the permissibility of slavery and concubinage is undeniable in the Quran. Rather than abolish sexual slavery, Brown asserts that Muslim jurists embraced the practice fully and took it to its maximum. He admits that the number of concubines taken by Muslims jumped dramatically with the early Islamic conquests. Brown also stresses that, in Islamic law, consent for sexual relations was assumed or irrelevant. Not only does he argue that sex slaves played a central role in Arab and Ottoman slavery, but he goes as far as to trivialize the age of consent. Moreover, he argues that freedom is not a fundamental human right in Islamic law, and treats serial polygamists who had hundreds of sex slaves as moral exemplars. Brown equates opposition to the institution of slavery and sexual servitude as opposition to the Messenger of God. He considers those who oppose slavery but refuse to condemn the Prophet to be hypocrites. When faced with dissenting views on the disputed subject of the legitimacy of slavery in Islam, Brown's strategy is to respond with a loaded trick question and a theological trap: Did the Prophet Muhammad commit a grave moral wrong? For Brown, a Muslim does not remain a Muslim if he or she answers in the affirmative.

Consequently, he provides a jurisprudential justification for the practice of Takfir, namely the excommunication of so-called heretics and apostates, and provides ample evidence that Muslims of a long history of enslaving other Muslims who do not share their ideology. Brown may claim to believe that slavery is wrong. However, he makes an important disclaimer: “As a Muslim myself, I cannot condemn it as grossly, intrinsically immoral across space and time. To do so would be to condemn the Quran, the Prophet Muhammad, and God's Law as morally compromised.” However, rather than support Islamic abolitionists, he assumes the role of the devil's advocate, devoting an inordinate amount of time in his book to dismissing, debunking, and repudiating their arguments as violating the Quran, the Sunnah, and the Sharia.

If one rejects the views of Muslim scholars who spurn slavery, is one an opponent or supporter of this evil and abominable institution? In fact, Brown wonders whether slavery is in the DNA of Islam. In his words, “we can't pretend it's not a part of our religion.”

Brown's entire work is an ideological defense of slave master Islam. That it comes from a white American Muslim is even more abhorrent.

This is the product of a conscious choice. His work is not simply a survey of historical opinions on the permissibility of enslavement, human bondage, sexual captivity, subjugation and violation. It is a validation of those views.

Alternative interpretations of Islam which are abolitionist and emancipatory are amply available. He is perfectly familiar with the arguments in evidence, namely that sexual relations are only permissible in wedlock and that the Prophet Muhammad stated that slave traders were the worst of human beings. Brown, however, has deliberately decided to denounce them.

The fact remains that there is not a single verse in the Quran that commands slavery. The verses that touch upon the topic are descriptive. They deal with a temporal socio-economic reality.

Slavery is neither an article of faith, nor is it a religious obligation. In fact, the Qur'an encourages and even requires Muslims to emancipate enslaved people. As far as the exponents of Islam's spiritual, moral, ethical, and egalitarian tradition are concerned, the Qur'an, the prophet in Islam, introduced this system that would reform the practice of slavery and abolish it entirely and forever.

Rather than select the sharp and narrow path, Brown has selected the wide and shallow one of the classical Islamic status quo. And since he likes to confront critics with a question, this review ends with a question, not of my own, but one that God poses in the Quran: What will make you know what the steep path is? It is the freeing of the slave.

So this is the short review. that I wrote for Reading Religion. The editor gets back to me and says, we cannot publish this review. And of course, I write articles, I publish articles, I'm very well published, I'm very well respected. And well, why? And she says, you're misrepresenting Brown's views. I say, have you read the book? She says, no. But I googled him.

Oh, wow. Rigorous methodology. And, you know, “I I have found a quote where he says that he thinks slavery is wrong.” And so I'm misrepresenting his views.

Now, some of those comments he made, he made them in 2017, and this book came out in 2019 and 2020. So I'm going to go with the book. Had he changed his mind on this subject, surely it should have been reflected in this text.

And so here we have a woman who is just so woke, okay? You have one person who's saying that slavery is in the DNA of Islam.

I don't agree with this. There is no place in the Qur'an where slavery is mandated, where it is made obligatory. It is not a matter of faith. It is not a matter of creed. One does not have to believe in slavery. There's all kinds of measures in the Qur'an to eradicate slavery. There's all kinds of traditions condemning slavery.

And there is a long history of Muslim scholars from the dawn of Islam, from the 7th century, all the way to our present time, hundreds and hundreds of them, who have condemned slavery, who said that this is not acceptable, this is against the morals and ethics of Islam.

But you have this woke editor who prefers to take the side of someone who's basically ISIS lite.

So, they wouldn't publish the review. Now I got really upset. I started to expand upon the review and it snowballed and it turned into a book which is called Islam and Slavery published by Academica Press based in Washington DC and London. My book is a scholarly response. And it's a work of righteous rage and indignation. It's an Islamic emancipation proclamation. That's the background of the book and how it came to be.

Islam is what Muslims do with Islam. Is there an imperialistic Islam? Sure, there were Islamic imperialists. Is there an emancipatory Islam? Is there an egalitarian Islam? A spiritual Islam? Absolutely.

So like which type of Islam do you want to, do you believe in? Do you want to disseminate? Do you want to promote? So again, this boils down to a choice. What are your basic fundamental ethical principles?

This is a public episode. If you’d like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit kevinbarrett.substack.com/subscribe

More Episodes

2023-05-28

2023-05-28

2023-05-27

2023-05-27

2023-05-14

2023-05-14

2023-05-13

2023-05-13

2023-05-06

2023-05-06

2023-04-30

2023-04-30

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2024 Podbean.com