NYC Starlets – Part 3: An Afternoon with Geri Miller, Warhol Super-Groupie and Sexploitation Actress – Podcast 138

2024-04-07

2024-04-07

Geri Miller may not be the most famous name from 1960s sex films, but she may well be the most interesting.

With a story that includes Andy Warhol, David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Joe Sarno, the Peppermint Lounge, Ringo Starr, Joe Dalessandro, Mick Jagger, James Brown, Jimi Hendrix, the Young Rascals, and stripping in front of the Queen Mother’s house, Geri lived a technicolor life in a psychedelic era.

The Rialto Report went to visit her.

This episode running time is 43 minutes.

—————————————————

Manhattan, 2024. It’s three o’clock on a damp afternoon on the Upper West Side, and, from down the block, I see Geri Miller holding court for anyone who will listen.

She’s in an electric wheelchair, the result of a fall a year ago, but otherwise looks well for her 81 years, even if at times her mental state is prone to wander precariously toward the outer limits of rationality.

I sidle quietly into her small group, which today consists of an African street seller of knock-off earphones, two sullen college kids collecting money for autism, and a barely-dressed homeless woman from Lithuania.

Today Geri is warning her audience of the dangers posed by transsexuals. It’s based on personal experience, stemming from memories of the late Candy Darling, actress and one-time muse of both Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground: “I knew Candy and his name was James, not Candy. Bet you didn’t know that, huh? I warned everyone back then. But did they listen? And now look what’s happening across the country.”

Her audience react to her triumphalism with a skepticism bordering on apathy, clearly ruing having selected to occupy that portion of sidewalk that day. Geri interrupts her flow when she sees me approach.

“Here’s someone who knows all about me,” she shouts triumphantly, pointing at me. “He knows the truth, and he’s here today to tell you all about it.”

*

It’s true. I’ve been fascinated with the life and times of Geri Miller for years. My interest started with her involvement in softcore sex films of the 1960s, though in truth, she wasn’t their biggest star: in fact, in sex movie history, she’s a minor footnote to other footnotes in a long-forgotten world. Yet paradoxically, it’s also true that Geri was possibly the most famous – and interesting – person who ever starred in sexploitation films.

She was a New York ‘It girl’ of her day, a B-level Edie Sedgwick, a precursor to Paris Hilton, a prototype Anna Nicole Smith, and a Gina Gershon-lookalike sexpot. She was glamorous, promiscuous, and ubiquitous, but above all, she was famous for being famous. Which usually means: famous for doing nothing in particular.

Except that Geri actually did stuff.

She was part of Andy Warhol’s Factory crowd, immortalized in his Polaroid art and appearing in his only play, the taboo-bending Pork (1971).

Geri and Andy Warhol

She was a self-described ‘Super Groupie’ – linked with members of the Beatles, and stars like Jimi Hendrix, David Bowie and James Brown. Her name was a staple in the syndicated newspaper gossip columns of the 1960s, which eagerly reported on who she was bedding that week.

She was frequently recognized on the streets, in diners, museums, and hotels, and hers was one of the first names added to any exclusive New York party list. (“Is Geri Miller coming to my birthday bash?” Mick Jagger once rhetorically queried, before rhetorically answering, “Would it really be a party without her?”)

She was a movie star of sorts: from small-time roles in big time movies (Stanley Kubrick’s Fail Safe (1965) alongside Walter Matthau and Henry Fonda) to bit parts in highly-regarded but highly invisible films (The Magic Garden of Stanley Sweetheart (1970) – Don Johnson’s gender-bending counter-cultural debut). She had starring turns in fleshy, trashy Warhol-conceived films, like Flesh (1968) and Trash (1970). And she was in fourteen sex films by the likes of luminaries (Joe Sarno) and ordinaries (Joel M. Reed and assorted anonymous one-film blunders.)

From the first time I saw her, furiously dancing the twist in a Maysles brothers’ documentary about the Beatles, I was hooked.

I wanted to know more.

Geri and Joe Dallessandro in ‘Flesh’ (1968)

*

I pry Geri away from her congregation suggesting we go grocery shopping. She eventually agrees, expertly operating the controls of her motorized wheelchair like a fighter pilot in an F-15 cockpit. She speeds down the block, starting conversation fragments with passersby and completely ignoring red traffic lights when she crosses the busy avenues (“don’t worry, the cars always stop when they see a wheelchair.”) Today she seems melancholic but grateful for the company: “I’m a star,” she says, “but no one believes it. I need you to prove it to people.”

I ask a question about the Peppermint Lounge, the legendary discotheque and celebrity hangout at 128 West 45th St where Geri was a regular house dancer. Is that where the Geri Miller story began – go-go dancing at the Peppermint in the 1960s? It wasn’t a good opener.

“It was not a go-go dancer!” she shrieks, bringing her chariot to an abrupt stop, glaring at me. “I was in the chorus line. I was a dancer. Trained in modern jazz dance because my parents were worried that I had knock knees! At the Peppermint, there were just four of us. There was Marlene, Misty, Janet, and me. And I was the only one who had formal dance training. We had two gay choreographers. Wake and Tom.” (A note for the curious: ‘Wake’ was Wakefield Poole. Yes – choreographer, dancer, and theatre director, but more notably, future director of Boys in the Sand (1971) and other groundbreaking gay porn films of the next decade.) The dancers developed a cult following in the club, formed a girl group, The Peppermints, for a hot moment, and cut a single, ‘We All Warned You’ for RSVP Recording Co.

Geri sets off again, grumbling – without any evidence – that she can’t talk and drive at the same time.

I ask her about the night of February 9, 1964, the occasion of the Beatles’ first Ed Sullivan appearance. The immediate aftermath of the Fab Four’s seismic performance was captured by Albert and David Maysles for a cinema verité documentary, ‘The Beatles: The First U.S. Visit,’ that covered the arrival of Beatlemania in the U.S. After the band dined at the Playboy Club, they made a pilgrimage to the Peppermint Lounge. The visit had mixed success: George left early with a sore throat, John and Paul looked cool relaxing at a table watching the house band, but for once, Ringo looked cooler, diving enthusiastically onto the dance floor, where he was joined by an equally energetic Geri.

Geri and Ringo, at the Peppermint Lounge

I ask Geri what she remembers about Ringo?

“Ugly and not very smart. That’s ok, I’m not smart either, but that’s why I like someone with a brain. All the girls wanted Paul, but I liked George. Too bad George left early is what I say. But I danced with Ringo, and then he asked me to join him at their table for the rest of the night. We had fun. Next day, I was all over the newspapers and magazines. I got calls, did interviews, the works.”

Cynthia & John Lennon, Ringo Starr, and Geri

I read Geri an article published in Photoplay Magazine in 1964 entitled ‘7 Days & 7 Nights With the Beatles’: “(The Beatles) especially enjoyed the Lounge. ‘We got a chance to talk to the chaps in the band and the dancers in the show,’ said John. Paul added, ‘It was good to be out with real people for a change.’ It was Ringo, however, who made out the best. He met pretty twister Geri Miller. He managed to keep her a secret, but it was Geri whom Ringo took home.”

I ask Geri if that was true? That she took Ringo back to her apartment that night? I quickly regretted the indiscreet question, given that, by now, we were being served at the salad bar of the local deli.

“Of course I took him back to my place. He may have been ugly and dumb, but he was still a Beatle! I didn’t have sex with him though. I just sucked his dick. I learned to do that with men I didn’t like much. A mob guy taught me. If it’d been George, I’d have gone all the way. Or maybe Paul. But not Ringo.”

Geri, I say. Keep your voice down, we’re in public.

She cackles hysterically. “What do I care? I sucked off a Beatle. Dick, dick, dick, dick, dick, dick!”

*

Geraldine Miller was born in April 1942. Her birth certificate records her parents as Mr. and Mrs. Morris Miller of Clifton, New Jersey, though Geri isn’t so sure. She says she doesn’t remember much about them, expressing indifference bordering on angry contempt when I ask for details. She spins vague yarns about Morris having been connected to the British royal family and emigrating to the States from England where he’d been a Charlie Chaplin impersonator. She points to her dark complexion as evidence that she is perhaps of mixed race. To listen to her theories about her parentage is bewildering, but it’s clear that the identity of her father is an anguished, recurring question that still exercises her.

Geri attended Clifton High School, graduating in 1960 (“I wasn’t popular: the girls were jealous of me because the boys wanted me, and the boys were intimidated by me”), and then she started a business and secretarial course at the local campus of a private school, Berkeley College. An only child, she was stifled and bored in Jersey. Worse, she felt unseen and ignored, and longed to perform under the bright lights of the big city. She frequently hopped the train and turned up in Manhattan where she put together a portfolio and auditioned for anything where she could be seen. Modeling, dance, theater, film work. Sometimes her efforts paid off: she got work as a ‘Seventeen’ model, and was chosen as ‘Miss Star of Tomorrow’ at Palisades Amusement Park from a group of over 500 girls.

In 1961, management at the Peppermint Lounge offered her a job as a dancer – correction, as a chorus line girl. She accepted on the spot, and kissed goodbye forever to New Jersey, Berkeley College, not to mention her disputed parents.

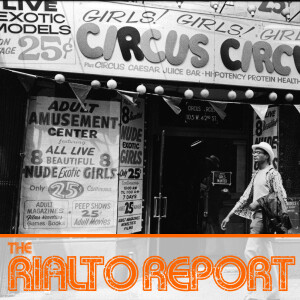

The timing of Geri’s arrival at the Peppermint was serendipitous: when she started work there, it was an unexceptional gay club, tucked away in a non-descript corner of Times Square. Relatively small (when full, the room catered to a capacity of 178 people), its primary purpose was to launder mob profits under the watchful eye of Genovese capo, Matty ‘The Horse’ Ianiello. (Sidenote: according to Geri’s personal experience, Matty’s nom-de-mob could not have been the result of his male endowment.)

And then, in a quirk of showbiz fate, The Peppermint exploded: the nationwide Twist craze hit, and the club’s house band, Joey Dee and the Starliters, released ‘Peppermint Twist.’ It spent three weeks at No. 1 in January 1962 which brought the club wide recognition, reinforced later in the year when Sam Cooke referred to it in his hit ‘Twistin’ the Night Away’ (“a place, somewhere up New York way, where the people are so gay”.) Overnight, celebrities swarmed into the club – real A-list celebrities too: Jackie O, Audrey Hepburn, Truman Capote, Marilyn Monroe, Judy Garland, Liberace, Noël Coward, Frank Sinatra, Norman Mailer, even the elusive Greta Garbo – all turning up to dance to Joey Dee’s hot twistin’ band.

In the blink of any eye, Geri was at the epicenter of New York night life, and she was as happy as a tornado in a trailer park. She was featured in gossip columns (“a 5’2”, 110-pound firecracker”) and offered modeling work. When film director Sidney Lumet went to the club, he approached her and offered her a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it part in his claustrophobic brink-of-doom, cold war drama, ‘Fail Safe.’ The Peppermint wasn’t just a magnet for glitterati: music bands were keen to play on its intimate stage, and soon the Beach Boys, the Four Seasons, the Isley Brothers, the Ronettes, the Crystals, even Liza Minnelli all played there.

Geri’s first screen appearance, dancing in Sidney Lumet’s ‘Fail Safe’ (1964)

One night in late 1962, James Brown stopped by and took a shine to Geri. He invited her to his show at the Apollo the following week where he was appearing with his band, the Famous Flames. It proved to be a landmark event: the show was recorded, and the resulting live album, ‘James Brown: Live at the Apollo’ (1963) became one of the biggest commercial and critical hits in recording history. Geri remembers the night well: “It was wild and loud in the theater. I’d never seen anything like it. And I was the only white girl there. I didn’t care. James showed me around, and I danced all night.”

James Brown and Geri started an on/off relationship which continued for years whenever he was in town: “I heard stories that he beat women, which was probably because his mother left him when he was small, but I never saw any of that. He was always good to me.” It was, however, a contentious liaison on both sides. Brown, who Geri remembers having a predilection for large-breasted girls, was often critical of his fellow black musicians when they consorted with white women, so he kept Geri hidden in hotel rooms. For her part, Geri knew that that the management at the Peppermint Lounge also frowned on interracial relationships because the goombahs feared negative publicity and… well, because they were just racist too. Geri remembers enduring low-level harassment at the club as a result.

When James Brown wasn’t around, she started dating Dino Danelli, drummer in a struggling rock group, The Young Rascals: “He had the blackest hair and the bluest eyes you’ve ever seen. Like if Paul McCartney came from Jersey.” Dino liked big-breasted girls too, but he said he’d make an exception for Geri. He moved into her apartment at 310 West 47th St – her Peppermint Lounge tips were more than his gig money after all. But then his band started having success, with number one hits like “Good Lovin'” (1966), “Groovin'” (1967), and “People Got to Be Free” (1968), and the Young Rascals became young rascals. Groupies started showing up, and Dino found it difficult to resist them: “He was the first guy to break my heart. I was so sad. We split, and he moved out and into his own place.” Today Geri still recites his 1964 phone number, still fresh in her mind.

The Young Rascals, with Dino Danelli, front right

Then James Brown asked her to marry him. Geri turned him down: “I said no, even though I loved him. The reason was that I was ashamed of my drug habit – which he knew nothing about. I was taking uppers all the time because I needed to keep up with… life. I was sad to turn him down, but I didn’t want him to find out.” Brown sent her a telegram, care of the Peppermint. It was intercepted by one of the managers who’d warned her against seeing Brown. Geri was dismissed the same day.

As for the Peppermint Lounge, it didn’t last much longer, closing down when it lost its liquor license on December 28, 1965.

*

Geri’s electric wheelchair sets off on the ten-block trip back to her apartment. She’s warming to the conversation, though she’s easily distracted by the street vendors. She crashes into a hat seller, and suggests I buy a fedora: “You need a hip new look,” is her sales pitch to me. I deflect, and ask about what she learned from her time at the Peppermint.

It turns out the Peppermint Lounge was formative in defining who Geri would be: She’d seen big stars first hand at the club – and slept with her fair share – and envied the money, adulation, and glamor. Now she wanted in. She wanted to be famous. For Geri, celebrity meant visibility, just as visibility meant celebrity. And visibility was what she craved after a life of anonymity. What she would be famous for was irrelevant: there was no need to create a brand in order to become a celebrity. Celebrity itself would be her brand.

So perhaps it was no surprise that Geri’s path would cross with that of Andy Warhol, crown prince of modern celebrity culture. He’d stopped by the Peppermint Lounge a few times to see what all the fuss was about, and whispered a question in her ear that resonated: how can something truly exist if no one is looking at it? Geri wanted to be seen, and so she and Andy formed a mutual appreciation group. Andy suggested she come to The Factory, his studio salon at 231 East 47th Street, creative home to various artists, musicians, and assorted eccentrics. Geri fit in perfectly and became part of the scene: she was a minor Warhol superstar perhaps, but a key component of the clique of idiosyncratic personalities promoted by Andy nonetheless.

Geri and Andy

Polaroids of Geri by Andy Warhol

In the meantime, Geri found work at the Metropole, the once-respected bebop jazz club which added strippers to its menu in the mid-1960s when patrons tired of its progressive music. This time, Geri admits, she wasn’t a chorus girl: she became a stripper. “I didn’t like it at first. I hated being topless, and so I took more uppers just to give me courage. It was difficult for me. I became promiscuous too. Oh boy, was I promiscuous. Especially when I did uppers. Everyone was just so glamorous.”

The Metropole (and three underwhelmed customers)

Conscious of James Brown’s and Dino Daneli’s preference for large breasted women, Geri paid for silicone injections: “I didn’t get implants. That’s when they put something in your chest. I just had injections. It wasn’t a big deal.” It didn’t stop the New York Daily News later describing her as “the lady with five pounds of silicone in each breast.”

For publicity, she targeted Earl Wilson, celebrity gossip journalist, respected and widely read. His column titled ‘It Happened Last Night’ ran in 175 newspapers nationwide. Wilson wrote about Geri for the first time in September 1966: she was a contestant for the prestigious ‘Miss Night Beat’ title and she’d heard that Wilson was one of the judges. So Geri dressed up in a daring outfit and turned up uninvited at his office, handing him pictures of herself in the buff. Wilson was tickled and charmed by her flirtatious chutzpah: whoever was awarded the ‘Miss Night Beat’ title is lost to irrelevant history, but Geri was the moral winner when Wilson described her racy visit to his estimated eighty million readers.

Andy Warhol approved of the risque’ publicity, and in 1968, he offered Geri a part in Flesh (aka ‘Andy Warhol’s Flesh’), the first of a trilogy of movies that would include Trash (1970) and Heat (1972). Directed by Paul Morrissey, it starred Joe Dallesandro as a bisexual street hustler who does tricks so that he can pay for his wife’s lover’s abortion. Geri played the part of… a topless dancer, appearing in a scene with fellow Warhol superstars Candy Darling and Jackie Curtis. She is strangely charismatic and compelling, giving Dallesandro head (shot from behind Dallesandro’s fully clothed standing body) and then delivering a lengthy story about being raped. Her monologue feels natural and improvised, even if the script reveals that she was closely following the dialogue written by Morrisey. In a memorable moment, Geri’s character admits she isn’t the smartest but is fine with that: “If I learn too much, I won’t always be happy. The more you learn, the more depressed you’ll be.” Today Geri insists: “That was my line! Andy overheard me say that, and so they added it to the script.”

‘Flesh’ falls somewhere between Factory home movie and early pornography. Predictably, it proved controversial, and was confiscated by New York police during early screenings at Warhol’s Garrick Theater. All publicity gravy to Andy and Geri.

Geri and Joe Dallessandro, in ‘Trash’ (1968)

Today, Geri’s memories of the film are less rosy. In fact, they’re overshadowed by the money she received. Or rather, the money she didn’t receive: “Andy only gave me $250 for that movie. Can you believe it? He ripped me off. He robbed me blind. And do you know how much money that film made? Millions probably. I was one of the stars. I get nothing today, and that film is still making money.” It’s a Hollywood grievance as old as the hills, but that doesn’t make it any easier for someone who’s fallen on hard times. Geri claims she pursued Warhol in later years, demanding an additional cut of the profits, but he wouldn’t even meet her.

“At least, I had sex with Joe D,” she says ruefully. “We took it home after the shoot. We had chemistry. Big time. You can see it in ‘Flesh’. Look at us kissing. That was art, and that was real.”

Geri throws back her head and laughs again.

*

And then came the sex films.

Admittedly they were softcore – black and white, pretty women/old men, bras cast off/panties kept on, giant Y-fronts and socks pulled up the knees – but still scandalous for the day. I ask Geri if she had any reservations making the racy films. The question feels naïvely ill-judged the moment I ask it. As if I hadn’t been paying attention. “Why would I care?” she replies. “I was a star, it was money, and it was easy work. I was a celebrity and I was good on screen.”

Geri’s right. There’s no such thing as bad publicity, and she’s always irresistibly watchable. She started in 1968 with a handful of bit parts: a pair of Joe Sarno moody melodramas, one of them called The Wall of Flesh in which she’s a hesitant participant in a group therapy orgy. Then there was Sex by Advertisement where she is raped and blackmailed in a lengthy scene (while trying, and failing, to keep a straight face.)

Geri in Wall of Flesh’ (1968), with (l-r) Janet Banzet, Irene DeBari, Cherie Winters

Geri in ‘Sex by Advertisement’ (1968)

In 1969, there were three more films: Meeting on 69th Street where, dressed in a mini-skirt and white go-go boots, she seduces her girlfriend’s man – at the same time that her girlfriend is schtupping him, no less. In Monique, My Love, she performs her Metropole stripping routine before playing with a coke bottle. And in Fly Now, Pay Later she’s a Moroccan courtesan seducing 1960s skin flick regular, Alex Mann.

Geri in ‘Meeting on 69th Street’ (1969)

Geri in ‘Monique, My Love’ (1969)

Geri in ‘Fly Now, Pay Later’ (1969)

I ask Geri about each one in turn but the memories have long departed. She never saw any of them she says, and has no recollections to share. She expresses surprise and delight at the movie scenarios that I describe for her but shrugs. Filming each one took less than an afternoon, she insists, and they were shot almost sixty years ago: “How in the fuck should I fucking remember them?” she reasons in an unreasonable way. “To be honest I doubt it is actually me on the screen. They do that, you know? They put your face on someone else’s body. That happens a lot. I never made all those films. That’s a lot of movies. No way I was in them all.”

There is one film that angers her, however. A while back, she saw her IMDb filmography and one item stood out: Daughters of Lesbos (1968), a movie in which she had starred as a dominatrix, ‘Dominique.’ “Impossible!” she shouts. “I never made that film!”

How do you know, I ask? After all, you don’t remember any of the others, so why is this one different?

“Because I’m not a lesbian!” she bellows in frustration. “I never did sex acts with another woman! So I was never in that film. It’s slanderous!”

She asks me to write to IMDb and have the film removed from their site. I try to reason with her: the films’ salacious names were often not matched by their content. Just because this particular title refers to ‘Lesbos’ doesn’t mean that Geri is engaged in sapphic fumbling. Geri is unconvinced.

I tell her I have copies of all her films on my laptop in case she has an interest in seeing any of them. She appears concerned to be confronted by the idea of seeing the evidence, before dismissing the idea: “Why would I want to see them anyway? Looking back at when I was young and beautiful isn’t going to do me any good.”

We’re standing outside a Chinese restaurant that has caught her eye. “This serves some of the best Chinese food in the city,” she says. “Why don’t we have some food?”

Geri on the one-sheet for ‘Daughters of Lesbos’ (1968)

*

If the late 1960s had been a dress-rehearsal for Geri, the early 1970s were her coming-out party.

First she appeared in Trash (1970), the second in the Warhol/Morrissey trilogy. Once again, Dallesandro stars, portraying a day in the life of a heroin addict, this time overdosing in front of an upper-class couple, attempting to fool welfare by having his girlfriend fake a pregnancy, and frustrating women with his drug-induced impotence. And once again, Geri is a highlight: she’s in a lengthy scene, unsuccessfully trying to arouse the movie’s anti-hero by dancing and singing ‘Mama, Look At Me Now,’ a song that would become a trademark theme for her. Geri claims her pay was the same as the first Warhol/Morrissey film: a meager $250.

Geri and Joe Dallessandro in ‘Trash’ (1970)

Andy and Geri

She did get better pay for appearing in other critically acclaimed films, such as The Magic Garden of Stanley Sweetheart (1970) about a New York gender-bending college dropout seeking his identity during the sexual revolution. It starred Don Johnson in his movie debut, and Warhol was so impressed with it, that he declared it represented “the quintessential, most truthful studio-made film about the ’60s counterculture”. Then Geri showed up in Pound (1970), Robert Downey Sr’s surreal, experimental film about eighteen dogs waiting to be adopted. And you can see her in a wild dance sequence in The Telephone Book (1971), where a victim of an obscene caller becomes obsessed with her fantasy of him. All small roles, but they generated enough stories to keep her name in the gossip columns for months. (In one newspaper article, she complained that she was profoundly ashamed of new naked photographs she’d had done – not because of the nudity but because she had an ugly hairdo.)

Geri was appearing all over town: she joined a cabaret show featuring fellow Warhol superstar, Eric Emerson, and his band the Magic Tramps, where she reprised ‘Mama, Look At Me Now’ from ‘Trash.’ She appeared on David Susskind’s investigative chat show where she was interviewed about life as a groupie. She upstaged the premiere of the Monty Python film, ‘And Now For Something Completely Different’ (1971), in a publicity stunt with a man in a gorilla costume. Tennessee Williams took her fishing. (Where does a playwright take a dancer fishing, I ask? “Fucking Brighton Beach, obviously!” is the answer.) And seriously, do you know anyone else who went on dates with David Cassidy and Jimi Hendrix?

She was still part of Andy Warhol’s Factory crowd too. Warhol gave her a walk-on in the latest Paul Morrissey effort Women in Revolt (1971) that starred fellow superstars Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis, and Holly Woodlawn. More importantly, Geri scored a role in Pork, the first and only Warhol theater play. ‘Pork’ opened on May 5, 1971, at La MaMa Experimental Theatre in New York City for a two-week run. As usual, a Warhol-sponsored event caused a furore, and the New York Times’ review commented on the excess “fornication, masturbation, defecation and prevarication.”

Geri in ‘Pork’ (1971)

Geri was asked to reprise her role when ‘Pork’ transferred to London, playing at the Roundhouse for a six-week run in August 1971. The Brits largely panned the play, though some critics insisted that its over the top obscenity wasn’t the problem but rather the point of the whole farrago. As one journalist wrote, “Pork’s redeeming essence is that it finds itself so ridiculous, that from start to finish, it demands not to be taken seriously. It’s Warhol people debunking themselves.”

Geri, in a publicity still for ‘Pork’

The U.K. production had some notable admirers: David Bowie went to see it several times and was impressed enough to hire several of the ‘Pork’ cast members to join his management firm, MainMan. Bowie even invited Geri to be his personal guest at his first New York show. (Sure enough, in October 1972, when Bowie made his New York debut at Carnegie Hall, Geri stormed the stage armed with gladioli to welcome him.) But probably the most press ink related to the play was spilled over a publicity stunt that Geri orchestrated: during a photo session in front of Clarence House, the Queen Mother’s residence, she exposed her breasts. Nudity in front of royalty? The local tabloids were outraged and joyfully lapped it up. Geri was arrested and threatened with deportation. Mission accomplished.

Geri in London, 1971

Back in New York, Geri was on a roll. In 1972, she jumped out of a cake at Mick Jagger’s birthday party at the St Regis (“the cake had three tiers, Geri was nude,” it was reported) before a guest list that included Count Basie, Muddy Waters, and Stevie Wonder.”Mick was good looking, but very average in bed,” is her volunteered report card.

Then she taunted Iggy Pop. Iggy and Geri had history: the previous year, Iggy had performed at Ungano’s in New York and grabbed Geri’s face, pulling her and her metal folding chair across the floor in a bizarre piece bit of stage theatre. The next time their paths crossed was at the Electric Circus where Iggy told the crowd they made him feel sick. “Let’s watch you puke then,” Geri shouted at him from the front row. Mr. Pop obliged – and threw up all over Geri.

Geri’s credits kept on coming: she was a featured attraction in The Flasher, a one-night Broadway show based on a porn film. She sang with glam-rock, satin-suited rock band Angel. Eric Burdon, formerly lead singer with the Animals, shipped her to Los Angeles to appear on his album. Each one of these events is a separate story of its own, but they’re just another day in Geri’s world.

Not that Geri ever stopped stripping. Her agent, the exotically-named Brooklyn Jew, Mambo Hi, made sure of that. Her list of ecdysiast employers reads like a history of 1970s burlesque in New York: she was still dancing topless at the Metropole on Seventh Ave., and in the afternoons, she found a gig at the M&M Lounge at 51 Little West 12th St (“a moribund area” said one newspaper.) It was a tiny club, with a 4×4 stage, catering to meat-packing workers. When she needed extra money, she danced at the Carnival at 146 West 45th St, former site of the Great Wall, a Chinese restaurant. From time to time, you could find her at Club 45, the Wagon Wheel, the Mardi Gras, the Rolling Stone, and the Coventry, on top of her occasional bar work at CBGB’s and Max’s Kansas City.

Geri also gave birth to a daughter who she put up for adoption. In the years ahead, regretting her decision, she would try to track her daughter down, but without success. It remains a source of sadness and frustration.

*

Somewhere along the road, the threads of Geri’s life started to unravel like a cheap sweater. Warhol’s generation of superstars were being ravaged by overdoses, suicide, or indifference. Party invitations slowed to a trickle before disappearing completely. Chat shows and gossip columns looked away, seeking new provocateurs. Rock stars found a new generation of groupies to have sex with. And strip clubs turned to younger women, asking them to do more than just strip.

So Geri took a radical and subversive step: she found a full-time nine-to-five job with crisp white collar legal firm, Shearman & Sterling. It may have been less fun, but the paycheck was regular and healthcare was an added bonus. Geri claims she was put to work on interesting cases, including the last will and testament of Winthrop Rockefeller, son of John D. Rockefeller. The job didn’t last: you can take the girl out of the limelight, but you can’t take the limelight out of the girl. One day, she revealed her back story to a paralegal at the firm. All of it, from Warhol, Jagger, and James Brown, to stripping, sex movies, and Super Groupie sex. Next day she found herself without employment. A complementary letter of recommendation from one of the legal partners who’d taken a shine to her wasn’t much of a consolation.

Then Geri got a job as assistant to Alice F. Mason, the legendary New York real estate broker and socialite. Mason was a powerbroker in the world of luxurious Manhattan apartments, advising the rich and wealthy on how to navigate the exclusive world of the city’s co-ops, particularly the upscale buildings lining Park and Fifth Avenues. Marilyn Monroe, Henry Kissinger, and Gloria Vanderbilt were among of her closest friends and dedicated clients.

Alice F. Mason

Today, Geri has a way with a conspiracy theory like a prisoner has a way with a file, so when she told me that Alice Mason had been hiding a secret life, I was skeptical: “Alice was the queen of white society. But I bet you didn’t know she was a black woman from a black family in a black neighborhood. She came from Philly. She started out as a dancer like me in the 1950s. And she only called herself ‘Mason’ because she liked the actor, James Mason. The ‘F’ in her name stood for ‘Fluffy’. Bet you didn’t know that.”

After Geri started work for Alice Mason, Alice confided to Geri that she’d been “passing” as white for decades so she could live her life in exclusive white New York social circles without facing the era’s prejudices toward people of color. It was a big secret, and one that Alice never shared with even her closest friends. It was a tall tale, but when I looked Alice F. Mason up I found that Geri’s story was correct – though the secret hadn’t been revealed until recently. It’s a pattern that reveals itself time and again with Geri: she tells a tall story usually involving a famous person and an unlikely situation. Like being James Brown’s secret lover or jumping out of a cake for Mick Jagger or appearing on stage with David Bowie or fishing with Tennessee Williams. And then I find a newspaper article substantiating it, or I speak to someone who was there and saw it happen. Geri’s certainly prone to flights of imagination, but she’s also had a surprising life.

Back in the 1970s, Geri liked Alice Mason, and the feeling was mutual. Alice encouraged Geri to get a real estate license and pursue a business career. “Time is of the essence,” Alice told her. Geri signed up, but their relationship ended one night when Alice told her to come over to her Upper East Side apartment and pick up some papers. When Geri arrived, Alice was waiting for her in bed. Geri spurned her advances and found herself unemployed again.

*

I ask Geri what happened next. She’s not one for self-reflection or self-pity, but admits that sometime in the following years, life became difficult. For whatever reason, she found it hard to hold onto a regular job and started living in homeless shelters. She remembers some of them (a battered women’s home in Park Slope in Brooklyn, a refuge on Park Avenue and another in the Village) but has forgotten most.

The intervening years have been a blur, more about survival that being a celebrity. She’s struggled with money and health, and in that respect is no different than many Americans. But occasionally, Geri returns to being an It girl again, albeit fleetingly, still attracting unexpected publicity. In 2021, Dave Davies, lead guitarist for the Kinks, tweeted his memory of a waitress “who had huge tits and she used to wiggle them around – an Andy Warhol actress – who moved her tits with muscles like a bodybuilder at Max’s Kansas City.” It went viral in a small-time way becoming Davies’ most popular tweet. A couple of years later, he followed up with a brief, sheepish video of himself imitating this waitress’ striptease routine, and this time, he revealed her identity: “Her name was Geri Miller, and she was good fun and a nice person.” I tell Geri about it. She shrugs and smiles: “Does he want to send me some money?” she sighs.

Today she lives in a sparsely decorated one-room apartment in an housing building for low income seniors with disabilities. As I prepare to leave, Geri returns to the subject of her father. I ask if she has any idea as to who he actually was?

“I have some ideas,” she offers. “Maybe Sammy Davis Jr. Or perhaps Frank Sinatra or Jerry Lewis. It could have been Charlie Chaplin, I suppose. I don’t know, but he’s out there somewhere.”

We pause as an ambulance passes, siren blazing loudly. Geri stares at it intently: “What if that’s my father coming to look for me? Can you can help me? We could look for him together.”

She sighs: “Or perhaps it’s true after all: the more you learn, the more depressed you’ll be.”

*

The post NYC Starlets – Part 3: An Afternoon with Geri Miller, Warhol Super-Groupie and Sexploitation Actress – Podcast 138 appeared first on The Rialto Report.

More Episodes

2017-12-03

2017-12-03

96

96

2017-11-12

2017-11-12

30

30

2017-09-24

2017-09-24

2017-09-03

2017-09-03

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2024 Podbean.com