The Nation’s Conscience, Part II - Read by Eunice Wong

2024-05-23

2024-05-23

Text Originally published May 08, 2024

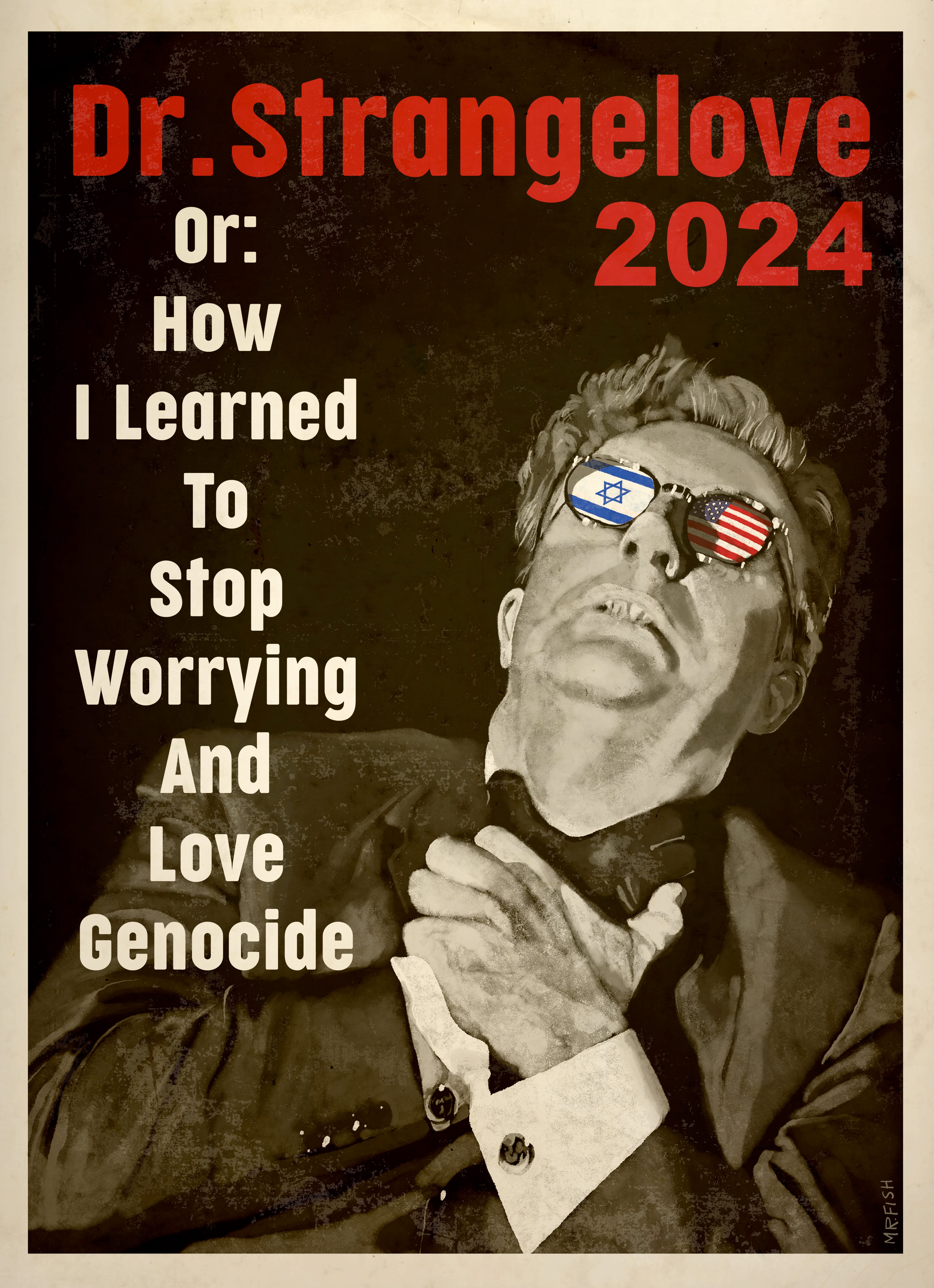

Strangelove 2024 — by Mr. Fish

University President Christopher Eisgruber met with the hunger strikers – the first meeting by school administrators with protesters since Oct. 7 – but dismissed their demands.

“This is probably the most important thing I’ve done here,” says Areeq Hasan, a senior who is going to do a PhD in applied physics next year at Stanford, who is also part of the hunger strike. “If we’re on a scale of one to 10, this is a 10. Since the start of encampment, I have tried to become a better person. We have pillars of faith. One of them is sunnah, which is prayer. That’s a place where you train yourself to become a better person. It is linked to spirituality. That’s something I’ve been emphasizing more during my time at Princeton. There’s another aspect of faith. Zakat. It means charity, but you can read it more generally as justice…economic justice and social justice. I’m training myself, but to what end? This encampment is not just about trying to cultivate, to purify my heart to try to become a better person, but about trying to stand for justice and actively use these skills that I’m learning to command what I feel to be right and to forbid what I believe to be wrong, to stand up for oppressed people around the world.”

Anha Khan, a Princeton student on hunger strike whose family is from Bangladesh, sits with her knees tucked up in front of her. She is wearing blue sweatpants that say Looney Tunes and has an engagement ring that every so often glints in the light. She sees in Bangladesh’s history of colonialism, dispossession and genocide, the experience of Palestinians.

“So much was taken from my people,” she says. “We haven’t had the time or the resources to recuperate from the terrible times we’ve gone through. Not only did my people go through a genocide in 1971, but we were also victims of the partition that happened in 1947 and then civil disputes between West and East Pakistan throughout the forties, the fifties and the sixties. It makes me angry. If we weren’t colonized by the British throughout the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth century, and if we weren’t occupied, we would have had time to develop and create a more prosperous society. Now we’re staggering because so much was taken from us. It’s not fair.”

The hostility of the university has radicalized the students, who see university administrators attempting to placate external pressures from wealthy donors, the weapons manufacturers and the Israel lobby, rather than deal with the internal realities of the non-violent protests and the genocide.

“The administration doesn’t care about the well being, health or safety of their students,” Khan tells me. “We have tried to get at least tents out at night. Since we are on a 24-hour liquid fast, not eating anything, our bodies are working overtime to stay resilient. Our immune systems are not as strong. Yet the university tells us we can’t pitch up tents to keep ourselves safe at night from the cold and the winds. It’s abhorrent for me. I feel a lot more physical weakness. My headaches are worse. There is an inability to even climb up stairs now. It made me realize that for the past seven months what Gazans have been facing is a million times worse. You can’t understand their plight unless you experience that kind of starvation that they’re experiencing, although I’m not experiencing the atrocities they’re experiencing.”

The hunger strikers, while getting a lot of support on social media, have also been the targets of death threats and hateful messages from conservative influencers. “I give them 10 hours before they call DoorDash,” someone posted on X. “Why won’t they give up water, don’t they care about Palestine? Come on, give up water!” another post read. “Can they hold their breath too? Asking for a friend,” another read. “OK so I hear there’s going to be a bunch of barbecues at Princeton this weekend, let’s bring out a bunch of pork products too to show these Muslims!” someone posted.

On campus the tiny groups of counter protesters, many from the ultra orthodox Chabad House, jeer at the protesters, shouting “Jihadists!” or “I like your terrorist headscarf!”

“It is horrifying to see thousands upon thousands of people wish for our deaths and hope that we starve and die,” Khan says softly. “In the press release video, I wore a mask. One of the funnier comments I got was, ‘Wow, I bet that chick on the right has buck-teeth behind that mask.’ It’s ridiculous. Another read, ‘I bet that chick on the right used her Dyson Supersonic before coming to the press release.’ The Dyson Supersonic is a really expensive hair dryer. Honestly, the only thing I got from that was that my hair looked good, so thank you!”

David Chmielewski, a senior whose parents are Polish and who had family interned in the Nazi death camps, is a Muslim convert. His visits to the concentration camps in Poland, including Auschwitz, made him acutely aware of the capacity for human evil. He sees this evil in the genocide in Gaza. He sees the same indifference and support that characterized Nazi Germany. “Never again,” he says, means never again for everyone.

“Since the genocide, the university has failed to reach out to Arab students, to Muslim students and to Palestinian students to offer support,” he tells me. “The university claims it is committed to diversity, equity and inclusion, but we don’t feel we belong here.”

“We’re told in our Islamic tradition by our prophets that when one part of the ummah, the nation of believers, feels pain, then we all feel pain,” he says. “That has to be an important motivation for us. But the second part is that Islam gives us an obligation to strive for justice regardless of who we’re striving on behalf of. There are plenty of Palestinians who aren’t Muslim, but we’re fighting for the liberation of all Palestinians. Muslims stand up for issues that aren’t specifically Muslim issues. There were Muslims who were involved in the struggle against apartheid in South Africa. There were Muslims involved in the civil rights movement. We draw inspiration from them.”

“This is a beautiful interfaith struggle,” he says. “Yesterday, we set up a tarp where we were praying. We had people doing group Quran recitations. On the same tarp, Jewish students had their Shabbat service. On Sunday, we had Christian services at the encampment. We are trying to give a vision of the world that we want to build, a world after apartheid. We’re not just responding to Israeli apartheid, we’re trying to build our own vision of what a society would look like. That’s what you see when you have people doing Quran recitations or reading Shabbat services on the same tarp, that’s the kind of world we want to build.”

“We’ve been portrayed as causing people to feel unsafe,” he says. “We’ve been perceived as presenting a threat. Part of the motivation for the hunger strike is making clear that we’re not the people making anyone unsafe. The university is making us unsafe. They’re unwilling to meet with us and we’re willing to starve ourselves. Who’s causing the un-safety? There is a hypocrisy about how we’re being portrayed. We’re being portrayed as violent when it’s the universities who are calling police on peaceful protesters. We’re being portrayed as disrupting everything around us, but what we’re drawing on are traditions fundamental to American political culture. We’re drawing on traditions of sit-ins, hunger strikes and peaceful encampments. Palestinian political prisoners have carried out hunger strikes for decades. The hunger strike goes back to de-colonial struggles before that, to India, to Ireland, to the struggle against apartheid in South Africa.”

“Palestinian liberation is the cause of human liberation,” he goes on. “Palestine is the most obvious example in the world today, other than the United States, of settler-colonialism. The struggle against Zionist occupation is viewed accurately by Zionists both within the United States and Israel, as sort of the last dying gasp of imperialism. They’re trying to hold onto it. That’s why it’s scary. The liberation of Palestine would mean a radically different world, a world that moves past exploitation and injustice. That’s why so many people who aren’t Palestinian and aren’t Arab and aren’t Muslim are so invested in this struggle. They see its significance.”

“In quantum mechanics there’s the idea of non-locality,” says Hasan. “Even though I’m miles and miles away from the people in Palestine, I feel deeply entangled with them in the same way that the electrons that I work with in my lab are entangled. As David said, this idea that the community of believers is one body and if one part of the body is in pain, all of it pains, it is our responsibility to strive to alleviate that pain. If we take a step back and look at this composite system, it’s evolving in perfect unitary, even though we don’t understand it because we only have access to one small piece of it. There is deep underlying justice that maybe we don’t recognize, but that exists when we look at the plight of the Palestinian people.”

“There’s a tradition associated with the prophet,” he says. “When you’ve seen an injustice occur you should try to change it with your hands. If you can’t change it with your hands then you should try to adjust it with your tongue. You should speak out about it. If you can’t do that, you should at least feel the injustice in your heart. This hunger strike, this encampment, everything we’re doing here as students, is my way of trying to realize that, trying to implement that in my life.”

Spend time with the students in the protests and you hear stories of revelations, epiphanies. In the lexicon of Christianity, these are called moments of grace. These experiences, these moments of grace, are the unseen engine of the protest movements.

When Oscar Lloyd, a junior at Columbia studying cognitive science and philosophy, was about eight-years-old, he and his family visited the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

“I saw the vast distinction between the huge memorial at the Battle of the Little Bighorn compared to the small wooden sign at the massacre at Wounded Knee,” he says, comparing the numerous monuments celebrating the 1876 defeat of the U.S. 7th Cavalry at the Little Big Horn to the massacre of 250 to 300 Native Americans, half of whom were women and children, in 1890 at Wounded Knee. “I was shocked that there can be two sides to history, that one side can be told and the other can be completely forgotten. This is the story of Palestine.”

Sara Ryave, a graduate student at Princeton, spent a year in Israel studying at the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies, a non-denominational yeshiva. She came face to face with apartheid. She is banned from campus after occupying Clio Hall.

“It was during that year that I saw things that I will never forget,” she said. “I spent time in the West Bank and with communities in the south Hebron Hills. I saw the daily realities of apartheid. If you don’t look for them, you don’t notice them. But once you do, if you want to, it’s clear. That predisposed me to this. I saw people living under police and IDF military threats every single day, whose lives are made unbearable by settlers.”

When Hasan was in fourth grade, he remembers his mother weeping uncontrollably on the 27th night during Ramadan, an especially holy day known as The Night of Power. On this night, prayers are traditionally answered.

“I have a very vivid memory of standing in prayer at night next to my mother,” he says. “My mother was weeping. I’d never seen her cry so much in my life. I remember that so vividly. I asked her why she was crying. She told me that she was crying because of all of the people that were suffering around the world. And among them, I can imagine she was bringing to heart the people in Palestine. At that point in my life, I didn’t understand systems of oppression. But what I did understand was that I’d never seen my mother in such pain before. I didn’t want her to be in that kind of pain. My sister and I, seeing our mother in so much pain, started crying too. The emotions were so strong that night. I don’t think I’ve ever cried like that in my life. That was the first time I had a consciousness of suffering in the world, specifically systems of oppression, though I didn’t really understand the various dimensions of it until much later on. That’s when my heart established a connection to the plight of the Palestinian people.”

Helen Wainaina, a doctoral student in English who occupied Clio Hall at Princeton and is barred from campus, was born in South Africa. She lived in Tanzania until she was 10-years-old and then moved with her family to Houston.

“I think of my parents and their journeys in Africa and eventually leaving the African continent,” she says. “I’m conflicted that they ended up in the U.S. If things had turned out differently during the post-colonial movements, they would not have moved. We would have been able to live, grow up and study where we were. I’ve always felt that that was a profound injustice. I’m grateful that my parents did everything they could to get us here, but I remember when I got my citizenship, I was very angry. I had no say. I wish the world was oriented differently, that we didn’t need to come here, that the post-colonial dreams of people who worked on those movements actually materialized.”

The protest movements - which have spread around the globe - are not built around the single issue of the apartheid state in Israel or its genocide against Palestinians. They are built around the awareness that the old world order, the one of settler colonialism, western imperialism and militarism used by the countries in the Global North to dominate the Global South, must end. They decry the hoarding of natural resources and wealth by industrial nations in a world of diminishing returns. These protests are built around a vision of a world of equality, dignity and independence. This vision, and the commitment to it, will make this movement not only hard to defeat, but presages a wider struggle beyond the genocide in Gaza.

The genocide has awakened a sleeping giant. Let us pray the giant prevails.

The Chris Hedges Report is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This is a public episode. If you’d like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit chrishedges.substack.com/subscribe

More Episodes

2024-01-01

2024-01-01

2023-11-16

2023-11-16

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2024 Podbean.com