- Podcast Features

-

Monetization

-

Ads Marketplace

Join Ads Marketplace to earn through podcast sponsorships.

-

PodAds

Manage your ads with dynamic ad insertion capability.

-

Apple Podcasts Subscriptions Integration

Monetize with Apple Podcasts Subscriptions via Podbean.

-

Live Streaming

Earn rewards and recurring income from Fan Club membership.

-

Ads Marketplace

- Podbean App

-

Help and Support

-

Help Center

Get the answers and support you need.

-

Podbean Academy

Resources and guides to launch, grow, and monetize podcast.

-

Podbean Blog

Stay updated with the latest podcasting tips and trends.

-

What’s New

Check out our newest and recently released features!

-

Podcasting Smarter

Podcast interviews, best practices, and helpful tips.

-

Help Center

-

Popular Topics

-

How to Start a Podcast

The step-by-step guide to start your own podcast.

-

How to Start a Live Podcast

Create the best live podcast and engage your audience.

-

How to Monetize a Podcast

Tips on making the decision to monetize your podcast.

-

How to Promote Your Podcast

The best ways to get more eyes and ears on your podcast.

-

Podcast Advertising 101

Everything you need to know about podcast advertising.

-

Mobile Podcast Recording Guide

The ultimate guide to recording a podcast on your phone.

-

How to Use Group Recording

Steps to set up and use group recording in the Podbean app.

-

How to Start a Podcast

-

Podcasting

- Podcast Features

-

Monetization

-

Ads Marketplace

Join Ads Marketplace to earn through podcast sponsorships.

-

PodAds

Manage your ads with dynamic ad insertion capability.

-

Apple Podcasts Subscriptions Integration

Monetize with Apple Podcasts Subscriptions via Podbean.

-

Live Streaming

Earn rewards and recurring income from Fan Club membership.

-

Ads Marketplace

- Podbean App

- Advertisers

- Enterprise

- Pricing

-

Resources

-

Help and Support

-

Help Center

Get the answers and support you need.

-

Podbean Academy

Resources and guides to launch, grow, and monetize podcast.

-

Podbean Blog

Stay updated with the latest podcasting tips and trends.

-

What’s New

Check out our newest and recently released features!

-

Podcasting Smarter

Podcast interviews, best practices, and helpful tips.

-

Help Center

-

Popular Topics

-

How to Start a Podcast

The step-by-step guide to start your own podcast.

-

How to Start a Live Podcast

Create the best live podcast and engage your audience.

-

How to Monetize a Podcast

Tips on making the decision to monetize your podcast.

-

How to Promote Your Podcast

The best ways to get more eyes and ears on your podcast.

-

Podcast Advertising 101

Everything you need to know about podcast advertising.

-

Mobile Podcast Recording Guide

The ultimate guide to recording a podcast on your phone.

-

How to Use Group Recording

Steps to set up and use group recording in the Podbean app.

-

How to Start a Podcast

-

Help and Support

- Discover

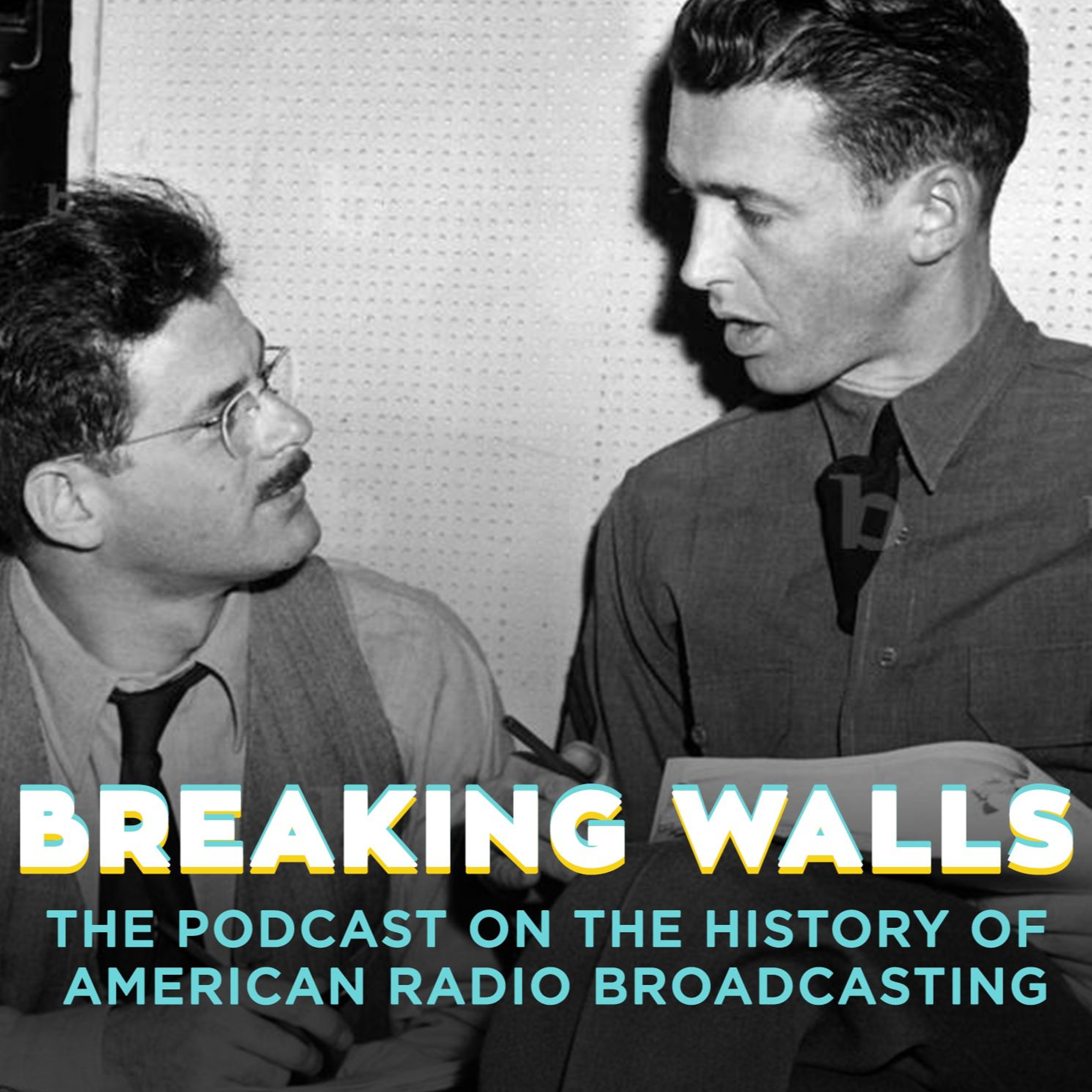

BW - EP153—001: Independence Day 1944—Norman Corwin From CBS To Pearl Harbor

2024-06-27

2024-06-27

More Episodes

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2025 Podbean.com