Andrée and the Aeronauts' Voyage to the Top of the World

2013-06-24

2013-06-24

Download

Right click and do "save link as"

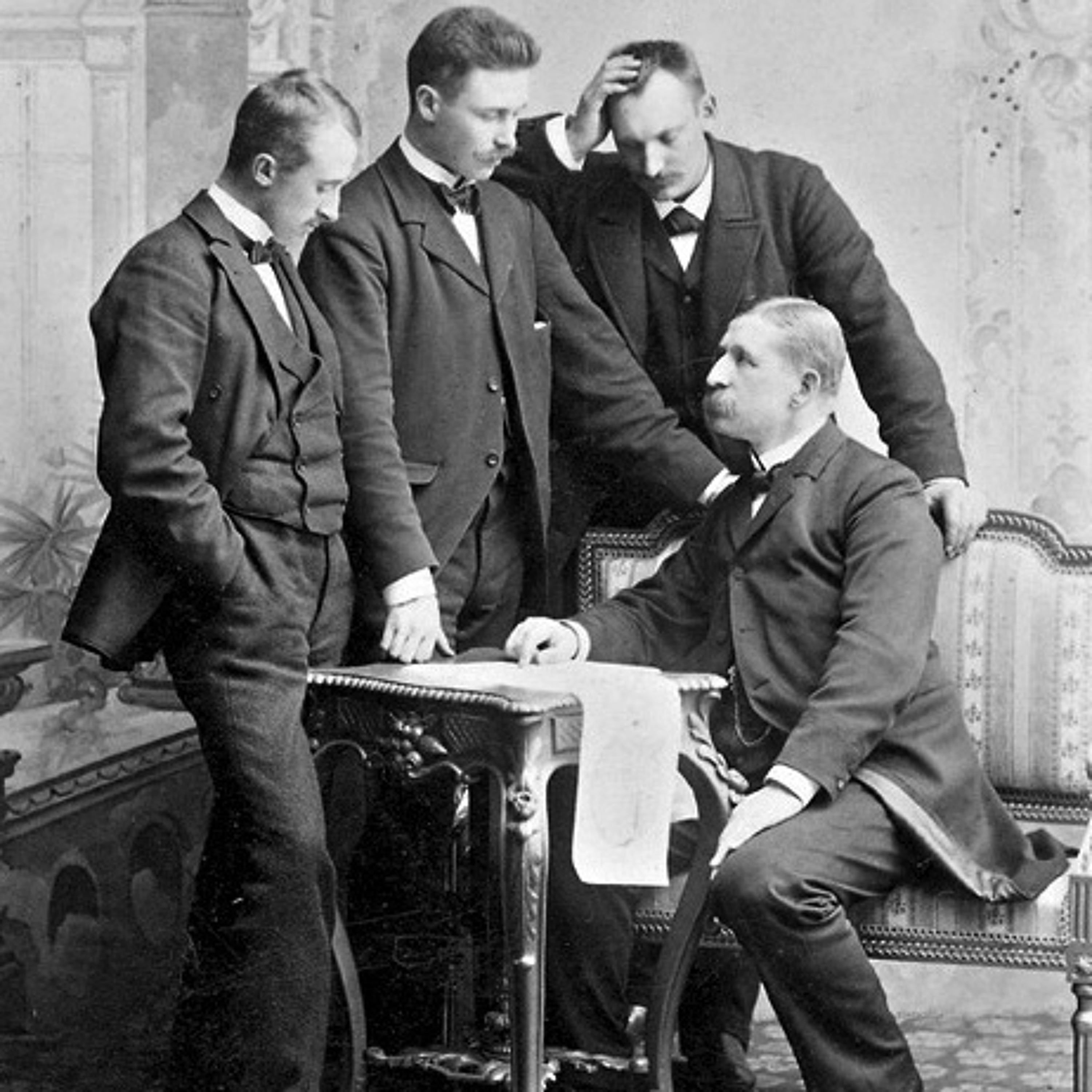

On the 11th of July 1897, the world breathlessly awaited word from the small Norwegian island of Danskøya in the Arctic Sea. Three gallant Swedish scientists stationed there were about to embark on an enterprise of history-making proportions, and newspapers around the globe had allotted considerable ink to the anticipated adventure. The undertaking was led by renowned engineer Salomon August Andrée, and he was accompanied by his research companions Nils Strindberg and Knut Fraenkel.

In the shadow of a 67-foot-wide spherical hydrogen balloon--one of the largest to have been built at that time--toasts were drunk, telegrams to the Swedish king were dictated, hands were shook, and notes to loved ones were pressed into palms. "Strindberg and Fraenkel!" Andrée cried, "Are you ready to get into the car?" They were, and they dutifully ducked into the four-and-a-half-foot tall, six-foot-wide carriage suspended from the balloon. The whole flying apparatus had been christened the "Örnen," the Swedish word for "Eagle."

"Cut away everywhere!" Andrée commanded after clambering into the Eagle himself, and the ground crew slashed at the lines binding the balloon to the Earth. Hurrahs were offered as the immense, primitive airship pulled away from the wood-plank hangar and bobbed ponderously into the atmosphere. Their mission was to be the first humans to reach the North Pole, taking aerial photographs and scientific measurements along the way for future explorers. If all went according to plan they would then touch down in Siberia or Alaska after a few weeks' flight, laden with information about the top of the world.

Onlookers watched for about an hour as the voluminous sphere shrank into the distance and disappeared into northerly mists. Andrée, Strindberg, and Fraenkel would not arrive on the other side of the planet as planned. But their journey was far from over.

view more

More Episodes

A Trail Gone Cold

2024-03-20

2024-03-20

2024-03-20

2024-03-20

Journey To The Invisible Planet

2023-06-13

2023-06-13

2023-06-13

2023-06-13

From Where The Sun Now Stands

2023-05-21

2023-05-21

2023-05-21

2023-05-21

The Ancient Order Of Bali

2023-03-28

2023-03-28

2023-03-28

2023-03-28

Lofty Ambitions

2022-12-13

2022-12-13

2022-12-13

2022-12-13

The Rube's Dilemma

2022-10-27

2022-10-27

2022-10-27

2022-10-27

Devouring The Heart Of Portugal

2022-05-03

2022-05-03

2022-05-03

2022-05-03

The Mount St. Helens Trespasser

2022-02-28

2022-02-28

2022-02-28

2022-02-28

Hunting For Kobyla

2022-02-07

2022-02-07

2022-02-07

2022-02-07

The Unceasing Cessna Hacienda

2021-10-25

2021-10-25

2021-10-25

2021-10-25

The Kingpin of Shanghai

2021-08-25

2021-08-25

2021-08-25

2021-08-25

The Traveler And His Baggage

2021-06-02

2021-06-02

2021-06-02

2021-06-02

Fifteen Years Forsaken

2021-04-27

2021-04-27

2021-04-27

2021-04-27

A Blight On Soviet Science

2021-03-02

2021-03-02

2021-03-02

2021-03-02

Pugilism On The Plains

2020-12-28

2020-12-28

2020-12-28

2020-12-28

Dupes and Duplicity

2020-09-04

2020-09-04

2020-09-04

2020-09-04

Chronicles of Charnia

2020-06-29

2020-06-29

2020-06-29

2020-06-29

The Spy of Night and Fog

2020-05-05

2020-05-05

2020-05-05

2020-05-05

Radical Solutions

2020-03-25

2020-03-25

2020-03-25

2020-03-25

012345678910111213141516171819

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2024 Podbean.com