93. Bulgaria’s Narrow Gauge Railway Winds Through History. Ivan Pulevski Helped Turn One of Its Station Stops Into a Museum.

2021-06-07

2021-06-07

Join the Club for just $2/month.

- Access to a private podcast that guides you further behind the scenes of museums. Hear interviews, observations, and reviews that don’t make it into the main show;

- Archipelago at the Movies 🎟️, a bonus bad-movie podcast exclusively featuring movies that take place at museums;

- Logo stickers, pins and other extras, mailed straight to your door;

- A warm feeling knowing you’re supporting the podcast.

Transcript Below is a transcript of Museum Archipelago episode 93. Museum Archipelago is produced for the ear, and only the audio of the episode is canonical. For more information on the people and ideas in the episode, refer to the links above.

Welcome to Museum Archipelago. I'm Ian Elsner. Museum Archipelago guides you through the rocky landscape of museums. Each episode is never longer than 15 minutes, so let's get started.

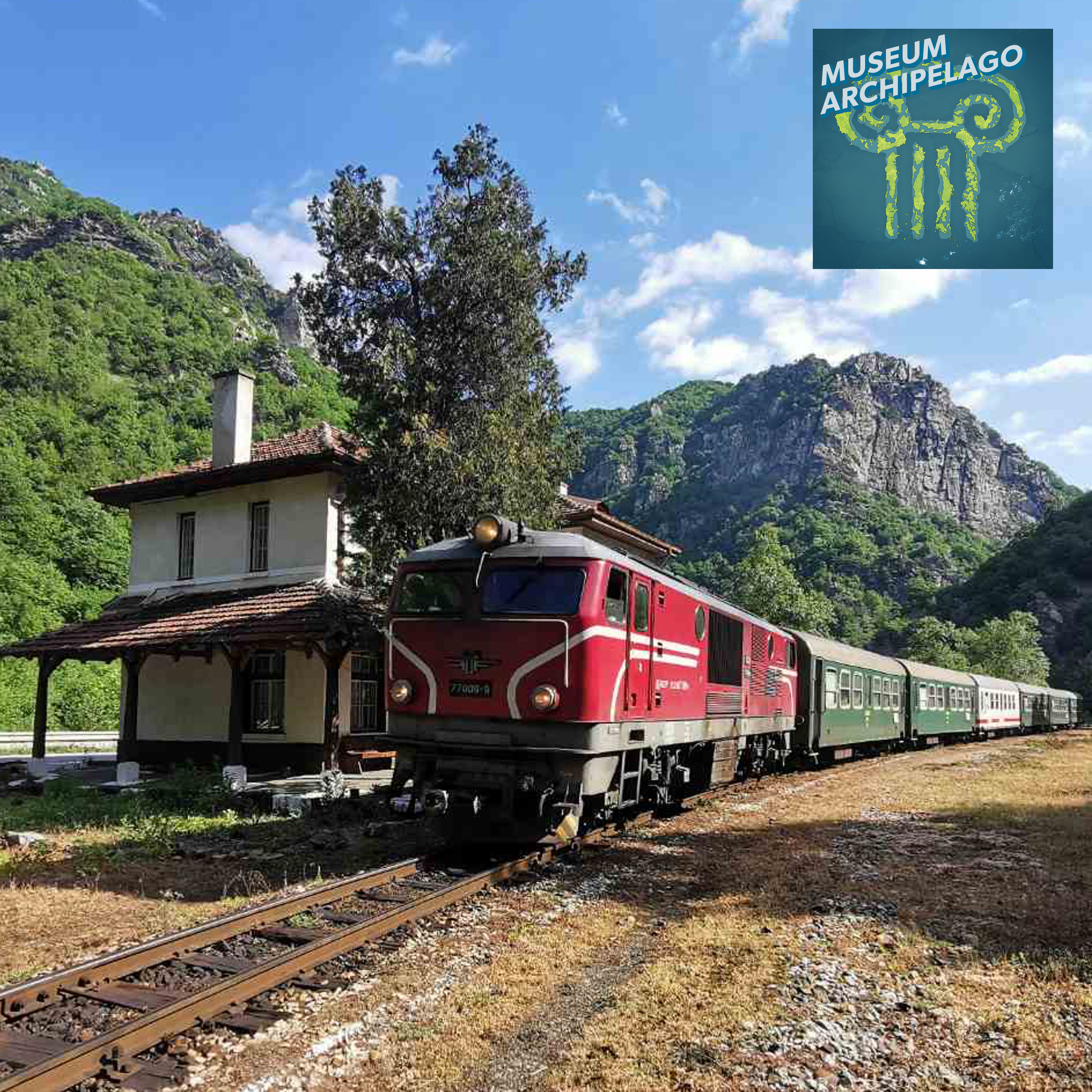

The waiting room of Tsepina Station, south of the Bulgarian city of Septemvri in the Rhodope mountains, sits under the watchful eye of portraits of Vladimir Lenin and Georgi Dimitrov -- the revolutionary communitst leaders of Russia and Bulgaria respectively. But the communist period is only one of the eras of Bulgarian history the narrow gauge railway winds its way through.

Construction on the railway, and the station, began in 1920, when a young Bulgarian Kingdom was concerned that the remote Rhodope mountains would be hard to defend against foreign invaders. Today, the railway is still a fixture of life in the region. Each day, 10 times a day, a diesel train passes by the station.

Ivan Pulevski: Many people rely on this railway because it's their only transport, their only way of transport, because there are many villages which has no road.

This is Ivan Pulevski, a train enthusiast who is also one of the founders of the House-Museum of the Narrow Gauge Railway, which sits inside Tsepina station.

Ivan Pulevski: Okay, my name is Ivan, Ivan Pulevski and I'm from Plovdiv. I'm currently a student in the Technical University of Sofia and I study transport technology and management.

Creating the railway through such mountainous terrain was a transport technology and management problem for 1920. The first two engineers who were invited by the government to plan the railway quit because of the technical difficulty of building it. Instead, the honor fell to a young engineer called Stoyan Mitov.

Mitov’s innovation was to build the railway in such a way that if you looked at it from above, the track would form numbers -- eights and sixes as the tracks pass over and under themselves to change elevation in such a tight space, The design also called for numerous tunnels.

Ivan Pulevski: This is actually a map of how it crosses. And it looks like eight. And these are two forms, which are more like six. So it was really, really complicated project: so all these tunnels. The railway actually has 35 tunnels.

In order to do that, the rail needed to be narrow gauge, which could handle the tight turning radiuses. The gauge refers to the distance between the two tracks of the railway: in this case, 760 mm. Every other working railway in Bulgaria today is standard gauge, with a distance between the tracks almost double that at 1,435 mm.

The painstaking construction continued for over two decades. Slowly, more and more villages and towns were connected to the rest of Bulgaria.

Ivan Pulevski: It was pretty primitive actually, because they didn't have multiple techniques and all the works were done by hand.

Finally, in 1939, the railway reached the Bulgarian town of Belitsa. To celebrate a more interconnected Bulgaria, none other than the Bulgarian King, Tsar Boris III drove the first locomotive to the city.

Ivan Pulevski: He was the only monarch in Europe who had a legal driving license for a train, for a steam engine. And the elderly people who still remember this moment say that they saw two miracles of their time: the train and the king.

The majority of the House Museum of the Narrow Gauge Railway concerns the daily functioning of the station after Tsar Boris III, and the beginning of the communist era in 1944. By 1945, the railway was complete in its current form, stretching from Septemvri to Dobrinishte.

Ivan Pulevski: It was actually probably the period in the timeline that the railway was at its peak. And in 1966 it had 71 trains per day.

The station’s waiting room is preserved with pictures and information about the different types of carriages and locomotives from the era. There’s a ticket counter window looking into the main control office of this station -- all using technology that was not regularly updated.

Ivan Pulevski: This station had no electricity and no water supply. So they used lanterns with gasoline and these phones, which are only connected to the Telegraph wire. And we still have no electricity.

As a result, the artifacts in the control office have an old-school charm -- you can see the hand-written diary of each train that came through, you can handle the heavy metal keys for the track switches, and you can even “validate” your ticket with the official heavy-duty ticket validation machine.

The station manager lived at the station, in rooms right above the control office and waiting room. Managers would get buckets of food and water delivered by train.

After the communist era collapsed in 1989, things got worse for the narrow gauge railway, and with no station manager, this station building fell into disrepair.

Ivan Pulevski: After the collapse of the communist era, many factories closed and actually the railway was not really maintained and the total abdication of the government made things so complicated that in 2003, all the freight trains were cut.

Pulevski’s organization, called “For the Narrow Gauge Railway” fought against cutting passenger services too.

Ivan Pulevski: Seven years ago they decided to cut some of the passenger friends as well. These people had no option to go home from work. Well, they have the train to go to work, but they did not have a train to go back. So fortunately, because a friend of mine who is actually part of our organization, decided to take some actions and the Bulgarian state-wide ways decided to put on track these trains as soon as possible.

As part of the cuts, stations like the one we’re standing at got removed from the schedules. In 2015, the organization “For The Narrow Gauge Railway” decided to do something with the abandoned building.

Ivan Pulevski: At first we decided not to make it a museum, but to just -- it was in really bad condition, so, decided to just fix some things. And then we had to think of a purpose. Why? Why we do this and decided to make it a museum, because it was the best solution. We don't have a museum for this railway.

The museum was created by Pulevski and other volunteers over the course of two years. The Bulgarian National Railway company repaired the station’s roof, and people donated money, time, and artifacts to be displayed in the museum.

Ivan Pulevski: In 2017, we opened the museum. It was a big opening actually. We had more than 100 guests at the time and it was really interesting, but unfortunately it's in the middle of nowhere, as you can see, and the maintenance -- it's hard.

The reasons for the maintenance issue are the same as the reasons for the railway in the first place.

Ivan Pulevski: We had a person, a retired person who used to come here to open the museum on the weekends, but he had some medical issues, so he does not come anymore. And since we are a voluntary organization, we did not have the funds for a salary of a person who will be here all the time. And also, there is no water supply or electricity, it is not the best place to work.

Today, a tour of the museum is available by appointment. The organization has acquired some display cases they hope to soon fill with more artifacts, and plans are in place to build a scale model of the station and surrounding railway.

But Pulevski is less interested in getting the museum officially accredited as a museum -- because that would come with all sorts of Bulgaria n museum regulations.

Ivan Pulevski: I shouldn't be saying this actually, but we are not a legal museum because in Bulgaria we have a procedure to be a museum. It's pretty complicated to be a museum in Bulgaria. The regulations sometimes are kind of left from years of socialism and actually they have even regulations for an expert to come to your museum and decide which object should be exposed. We wanted to make a museum for the narrow gauge railway. Why would a person who's an expert, but well, we can argue about that here and say, “okay, this and this and this.”

The best museum’s I visited are just like small museums made from the ground. Because of somebody who is really passionate about the topic or the museum.

Pulevski and the other volunteers hope that the museum, which is now adjacent to a road, becomes a place for motorists to stop, learn about the railway, and hopefully consider taking the train for their next journey.

Ivan Pulevski: The railway itself is that it is not only an attraction because the people still use this training. And it is part of the experience of seeing these people using the train every day, sharing their emotions, their worries, et cetera.

This has been Museum Archipelago.

You love Museum Archipelago. But maybe you don’t love that each show is only 15 minute. Now, there’s a way to support the show while getting more.

By joining Club Archipelago, you get access to hour-long episodes where I dive deep into pop culture about museums — movies like 2006’s Night at the Museum, 1966’s How To Steal A Million, and 2001’s Atlantis: The Lost Empire — with friends and fellow museum folks. It’s a lot of fun!

If you want to kick back and listen to a whole lot more about how pop culture reflects museums back to us, join Club Archipelago today for $2 a month at jointhemuseum.club. Thanks for listening.

For a full transcript of this episode, as well as show notes and links. Visit museumarchipelago.com. Thanks for listening. And next time, bring a friend.

More Episodes

2024-09-23

2024-09-23

2023-07-31

2023-07-31

2022-11-28

2022-11-28

2022-08-08

2022-08-08

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2024 Podbean.com