On this day in labor history, the year was 1952.

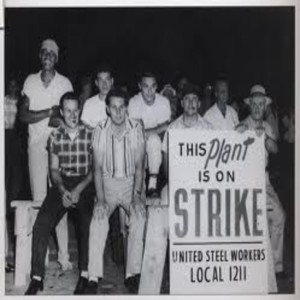

That was the day 650,000 steel workers walked off the job in an industry-wide strike.

The Supreme Court had just handed down a 6-3 ruling in the case of Youngstown Sheet & Tube v. Sawyer.

The court decided that the President had no authority to seize private property on the grounds of national security without prior authorization from Congress.

On April 4, President Harry Truman had issued Executive Order 10340, ordering Commerce Secretary Charles Sawyer to seize the nation’s steel mills to ensure the continued production of steel, ostensibly for the war effort.

Seizure of the mills came after months of wrangling over wage increases and work rules between mill owners, the United Steelworkers and the Wage Stabilization Board.

Steel workers walked out just hours after the decision.

The impact was felt immediately. Lay-offs began at a number of steel-dependent industries.

By the end of the month, most defense industries and auto plants nationwide were completely shut down.

Consumer inventories of steel were almost totally depleted and exports ceased entirely.

The union’s ultimate goal was a master contract and the union shop.

They hoped to jump start negotiations by signing with the smaller companies first and forestall invoking of Taft-Hartley.

By July, the railroads began to suffer financial losses, as did California growers who lacked tin to can their crops.

After 53 days, mill owners and the union agreed to terms that were less than what the Wage Stabilization Board had recommended, far less than what the union had originally demanded, but much more than what the mill owners had been willing to concede.

More importantly, after 15 years of struggle, the United Steelworkers had finally won the union shop.

More Episodes

2022-12-15

2022-12-15

2022-12-13

2022-12-13

2022-12-12

2022-12-12

2022-12-10

2022-12-10

2022-12-08

2022-12-08

2022-12-07

2022-12-07

2022-12-06

2022-12-06

2022-12-05

2022-12-05

2022-12-04

2022-12-04

2022-12-03

2022-12-03

2022-12-02

2022-12-02

2022-12-01

2022-12-01

2022-11-30

2022-11-30

2022-11-28

2022-11-28

2022-11-27

2022-11-27

2022-11-26

2022-11-26

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2024 Podbean.com