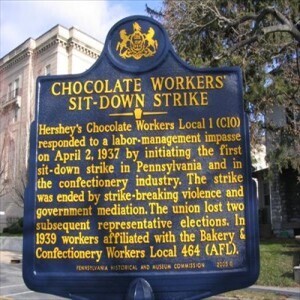

That was the day workers sat down at the Hershey chocolate plant in Hershey, Pennsylvania.

CIO organizers for the new United Chocolate Workers Union reported that anywhere from 2000-2400 workers were on strike.

Hershey was a company town, where streets were named Chocolate and Cocoa Avenue.

Housing was built for workers and the company funded public education and transit service.

But the company also sought to monitor and control workers behavior on their off-time and showed favoritism in hiring and wages.

The Great Depression created dire conditions even in Candy Land. Hours and bonuses had been cut.

Workers grew increasingly frustrated with production speed-up and unpredictable work schedules.

All while Hershey still drew handsome profits.

The company initially raised wages after meeting with the union but then laid off organizers three months later.

That’s when workers shut off their machines and occupied the plant.

The company refused to negotiate unless workers left.

By April 7, dairy farmers became incensed at the loss of income.

They mobilized with anti-union company forces to storm the factory and drive the strikers out.

Organizers had agreed to end the strike in order to resume negotiations and avert violence.

But the anti-union forces attacked the sit-downers with bats, whips, clubs and hammers.

Three CIO organizers were singled out and severely beaten.

Governor George Earle condemned the attack and blamed the County Sheriff for suppressing labor rather than preventing mob rule.

The strike was smashed. Attempts at installing a company union failed soon after.

Hershey’s would be one of the first candy companies to be organized when the Bakery, Confectionary, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union won recognition two years later.

More Episodes

2024-06-23

2024-06-23

2024-06-23

2024-06-23

2024-06-16

2024-06-16

2024-06-16

2024-06-16

2024-06-16

2024-06-16

2024-06-16

2024-06-16

2024-06-16

2024-06-16

2024-06-16

2024-06-16

2024-06-09

2024-06-09

2024-06-09

2024-06-09

2024-06-09

2024-06-09

2024-06-09

2024-06-09

2024-06-02

2024-06-02

2024-06-02

2024-06-02

2024-06-02

2024-06-02

Create your

podcast in

minutes

- Full-featured podcast site

- Unlimited storage and bandwidth

- Comprehensive podcast stats

- Distribute to Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and more

- Make money with your podcast

It is Free

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Terms of Use

- Consent Preferences

- Copyright © 2015-2024 Podbean.com